SONNETS 106-117

Sonnet 106

When in the Chronicle of wasted time,

I see descriptions of the fairest wights,

And beauty making beautiful old rhyme,

In praise of Ladies dead, and lovely Knights,

Then in the blazon of sweet beauty’s best,

Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow,

I see their antique Pen would have expressed,

Even such a beauty as you master now.

So all their praises are but prophecies

Of this our time, all you prefiguring,

And for they looked but with divining eyes,

They had not still enough your worth to sing:

For we which now behold these present days,

Have eyes to wonder, but lack tongues to praise.

Sonnet 106 addresses the relation between the ‘beauty’ of the youth and the

limited ability of words to represent his ‘worth’. The full ‘beauty’ of life, the

myriad of sensations and singular ideas, can only be hinted at in poetry. This

is a constant theme throughout the 154 sonnets. They argue for the priority

of the physical world over the world represented in books.

In sonnet 106, the Poet reads the ‘Chronicle of wasted time’ (106.1) and

imagines the ‘beauty’ of ‘Ladies dead, and lovely Knights’ (106.4) of times

gone by. Their ‘beauty’ inspired antique poets to write ‘beautiful rhyme’.

But the Chronicle cannot record the ‘worth’ of the complete person when

it transmutes their external beauty into ‘beautiful old rhyme’ (106.3).

The Poet can see how ‘even such a beauty’, which the youth ‘masters

now’ (106.8), would be reduced to mere words by ‘antique Pens’ (106.7).

When he looks at the words arranged on the page, such as ‘hand, foot, lips,

eye, and brow’ (106.6) they seem like the emblems blazed on (106.5) a coat

of arms or similar device.

All the ‘praises’ of the poets of old are but ‘prophecies of this our time’

(106.10) because, even today, words remain words. Even if they looked with

‘divining eyes’ they would still not be able to say enough to ‘sing’ the youth’s

real ‘worth’ (106.12). A Chronicle can only create a word image of how

things were then or how things are now. The process of physical increase

down the generations that connects the ‘worth’ of those days with the

‘worth’ of the youth ‘now’ cannot be captured in words.

In the couplet, ‘we’ who are alive ‘now’ can use our ‘eyes to wonder’ at

the full potential of the living youth. Such potential cannot be adequately

put into words because we ‘lack tongues to praise’ its living ‘worth’. In

Hamlet, Shakespeare famously addresses the inadequacy of ‘words, words,

words’ because they are secondary to the dynamic of life.

In previous sonnets the words ‘Pen’, ‘tongue’, ‘eyes’, have doubled as

sexual puns. With these puns Shakespeare evokes the physical dimension

mere words lack. He cannot emulate the physical process of life with words

but he can use puns to suggest its ‘worth’. The puns are also a warning for

those who wish to misread the Sonnets. Yet editors persist in making changes

to words that do not conform to their preferred reading of the youth as an

ideal beauty. They revert to an early version of sonnet 106 (from before

1599) that had ‘skill’ in line 12. They reject Shakespeare’s more precise

meaning for the 1609 edition that, whatever words evoke, they ‘still’ cannot

replace the youth’s natural worth.

Sonnet 107

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul,

Of the wide world, dreaming on things to come,

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Supposed as forfeit to a confined doom.

The mortal Moon hath her eclipse indured,

And the sad Augurs mock their own presage,

Incertainties now crown them-selves assured,

And peace proclaims Olives of endless age.

Now with the drops of this most balmy time,

My love looks fresh, and death to me subscribes,

Since spite of him I'll live in this poor rhyme,

While he insults o'er dull and speechless tribes.

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants' crests and tombs of brass are spent.

Shakespeare lived at a time when the sectarian conflict between Catholic

and Protestant, and the advance of science (epitomised by Bacon’s scientific

method and his tirade against the worship of idols), may have encouraged

him to develop his consistent philosophy based in nature. Sonnet 107, as

part of the truth and beauty sequence to the youth, contributes to the

expression of Shakespeare’s nature-based philosophy. But because commentators

are ignorant of sonnet 107’s philosophic purpose, they have instead

written volumes about the identity of ‘the mortal Moon’ as Queen

Elizabeth, or about the Spanish Armada in formation, and even the idea that

line 12 refers to the rebellion of the Earl of Essex.

The content of sonnet 107 is revealed when it is related to the philosophy

of the whole set. Particularly important for understanding the role of the

mortal Moon is the priority the Sonnets give to the female over the male.

The Poet’s ‘true love’ (107.3), or his feelings based in the persistence of

humankind, cannot be ‘controlled’by his own ‘fears’, or the ‘prophetic soul’

(107.1) of a world that spends more time ‘dreaming on things to come’ than

enjoying ‘the drops of this most balmy time’ (107.9). The ‘lease’ on his love

cannot be ‘forfeited’ to a ‘confined doom’ (107.4), or a belief that ‘prophesises’

the doom of humankind to enhance the ‘dream’ of everlasting life.

In the logic of the Sonnets the ‘mortal Moon’ (107.5) refers to the 28

Mistress sonnets. The number 28 identifies the Mistress with the lunar cycle

of womanhood. By the same logic, the Mistress also has priority over the

youth or male. So line 5 suggests the ‘mortal Moon’ has ‘endured’ or survived

her ‘eclipse’ by the male God. The ‘sad Augurs’ (107.6) that predicted her

‘doom’ now mock those predictions by their own failure. When compared

with the instability of the Church, the ‘uncertainties’ once attributed to

‘Mother Nature’ can ‘now crown themselves assured’.

Once the female is restored to her rightful place, ‘peace proclaims Olives

of endless age’ (107.8). The Poet’s ‘love looks fresh’ (107.10) because it is

renewed from generation to generation. ‘Death’now ‘subscribes’ to the Poet

because to ‘spite’ death (107.11) his poetry acknowledges the persistence of

life. ‘Death’ is accused of ‘insulting’ the intelligence of supposedly ‘dull and

speechless tribes’ (107.12), who live in harmony with nature.

The couplet affirms the youth will ‘find thy monument’ in the content

of the Poet’s verse. As in sonnet 55, it is the ‘content’ of the verse and not

the verse itself that survives. Books perish along with ‘tyrants crests and

tombs of brass’ while the mortal Moon rises again and again.

Sonnet 108

What's in the brain that Ink may character,

Which hath not figured to thee my true spirit,

What's new to speak, what now to register,

That may express my love, or thy dear merit?

Nothing sweet boy, but yet like prayers divine,

I must each day say o'er the very same,

Counting no old thing old, thou mine, I thine,

Even as when first I hallowed thy fair name.

So that eternal love in love's fresh case,

Weighs not the dust and injury of age,

Nor gives to necessary wrinkles place,

But makes antiquity for aye his page,

Finding the first conceit of love there bred,

Where time and outward form would show it dead.

In Shakespeare’s philosophy the body, or its persistence through the increase

process, is logically prior to the mind, or the possibility of understanding as

truth and beauty. The Poet’s ‘true spirit’ (108.2), or sense of life, is already

‘figured’ in the youth’s ‘brain’ (108.1). There is ‘nothing’ (108.5) in the

youth’s brain, or his own brain, that the Poet can express, which is not

logically prefigured in the body. There is nothing ‘new to speak’ or to

‘register’ (108.3) that ‘Ink may character’ that is better able to express the

Poet’s ‘love’ or the ‘dear merit’ (108.4) of the youth. Their ‘love’ is selfevident

in the relation between the body and mind. ‘Ink may character’

(108.1) the relation but can say ‘nothing’ new.

Yet the Poet, as a person with a mind aware of truth and beauty, wants

to write. But his poetry seems no more than ‘prayers divine’ (108.5), because,

logically, he must repeat ‘the very same…each day’ (see sonnet 76). His

sonnets mimic the rhythm of life where youth follows youth, generation

after generation. Because the Poet was also once young, he counts ‘no old

thing old’ (108.7). He identifies with the youthful potential of youth, ‘thou

mine’, just as the youth identifies with his old age, ‘I thine’. The Poet corrects

the illogical emphasis of the biblical ‘hallowed be thy name’ to recall the

moment when he ‘first hallowed thy fair name’ (108.8). Naming is the

‘hallowing’ of a newborn because the dynamic of language derives from the

dynamic of life. Shakespeare suggests that prayer makes no sense apart from

the natural rhythms of life.

By understanding the natural logic between the first ‘naming’ and saying

‘nothing’, the Poet is able to relate the ‘old’ idea of ‘eternal love’ to the

increase process. If love is renewed every generation in a ‘fresh case’ or body

(108.9), it should not feel the weight of death’s ‘dust’ or the ‘injury of age’

(108.10). By making ‘antiquity’, or past generations, his ‘page’ (108.12) or

paper, he can write with sense even if he repeats himself.

In the couplet, by combining the sense of writing on a ‘page’, and the

progression through ‘antiquity’ to the present day, the Poet sees the act of

naming, or ‘first conceit’, as being logically related to the idea of being ‘bred’.

This is contrary to old beliefs, based on ‘time’ and ‘outward form’, that the

youthful body is best shown ‘dead’. While Shakespeare says he has ‘nothing’

to say because all is evident in the youth’s ‘brain’, he is pointing to a positive

source of inspiration in life superior to the implicit death wish of the old

system of prayer.

Sonnet 109

O never say that I was false of heart,

Though absence seemed my flame to qualify,

As easy might I from my self depart,

As from my soul which in thy breast doth lie:

That is my home of love, if I have ranged,

Like him that travels I return again,

Just to the time, not with the time exchanged,

So that my self bring water for my stain,

Never believe though in my nature reigned,

All frailties that besiege all kinds of blood,

That it could so preposterously be stained,

To leave for nothing all thy sum of good:

For nothing this wide Universe I call,

Save thou my Rose, in it thou art my all.

Throughout the Sonnets, the theme of ‘absence’ (109.2) is a metaphor for

the age difference between the older Poet and the youth (see sonnets 50/51).

Invariably the Poet also takes account of the distance he ‘travels’ (109.6) from

the idealistic expectations of his younger ‘self ’ to his mature understanding.

The Poet knows that if he represents the relation to his youthful experiences

correctly he addresses the logical requirement for maturity.

The Poet’s ‘soul’ (109.4), or imaginary mind, lies in the ‘breast’ of the

youth. The knowledge gained by the Poet as a youth, remains an integral

part of his mature understanding. He cannot ‘depart’ from the youthful spirit

he once knew, even though ‘absence’ has qualified his ‘flame’ (109.2), or

reduced his capacity for passion. His truth to the spirit of youth means it

can ‘never’ be said he was ‘false of heart’ (109.1). The youth is his ‘home of

love’ (109.5) because that is where he inherited the possibility of love. The

mature Poet ‘returns’ to the youth from his ‘travels’ (109.6) because life

persists through the spirit of youth.

To remove the ‘stain’ of youth the Poet returns ‘to the time’ (109.8) when

he was young. Because his youth is a part of him, he does not view dying

as a period of ‘time exchanged’ for some other time. He ‘brings’ his own

‘water’ to baptise the ‘stain’ (109.7), or cleanse youth’s willfulness toward life.

The ‘stain’ is the tendency in youth to be beguiled by excessive idealistic

expectations. Shakespeare turns the stain of original sin around to identify

the real stain as the excessive idealism that leads to natural increase being

characterised as evil. After all, every human being alive was, is, and will be

increased into the world.

The ‘frailties’ (109.10) that ‘reigned’ in the Poet’s youthful nature ‘besiege

all kinds of blood’ relations or life based on increase (compare 67.9). There

is ‘nothing’, though, that can ‘so preposterously be stained’ (109.11), or so

unnaturally determined against life, that it can ‘leave for nothing’ youth’s

‘sum of good’ (109.12). As long as youth persists there is hope.

The couplet repeats the theme of sonnet 14, which rejects the stars of

heaven in favour of the truth and beauty in the eyes of the youth. The Poet

calls the ‘wide Universe’ ‘nothing’ compared with the youth who is his

‘Rose’. The Poet’s ‘Rose’, or the beauty associated with increase in the first

two lines of sonnet 1, is his ‘all’. In Shakespeare’s philosophy there can be

no maturity or completeness without first acknowledging the need to

perpetuate human life.

Sonnet 110

Alas 'tis true, I have gone here and there,

And made my self a motley to the view,

Gored mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear,

Made old offences of affections new.

Most true it is, that I have looked on truth

Askance and strangely: But by all above,

These blenches gave my heart another youth,

And worse essays proved thee my best of love,

Now all is done, have what shall have no end,

Mine appetite I never more will grind

On newer proof, to try an older friend,

A God in love, to whom I am confined.

Then give me welcome, next my heaven the best,

Even to thy pure and most most loving breast.

In the early 1590’s Shakespeare gave expression to his consistent philosophy

of life in poems such as Venus and Adonis and Lucrece, and in the early plays.

His decision to articulate the philosophy in a set of numbered sonnets was

most likely influenced by the publication at the time of sonnet sequences

by other poets. He had included sonnets in Romeo and Juliet, and the basic

ideas behind sonnet 14 are paraphrased in Love’s Labour’s Lost. The decision

to present his philosophy in a dedicated sonnet sequence released the plays

from the requirement to present a structured philosophic argument. The

plays were free to develop theatrically and dramatically, with the philosophy

acting as the underlying motive force.

By the time Shake-speares Sonnets were published in 1609, they had been

arranged into a highly systematic expression of his philosophy. The difficulty

commentators have in understanding individual sonnets is directly

related to their inability to appreciate the philosophy of the set. Most have

dismissed Shakespeare as having no philosophy, and the Sonnets are seen as

autobiographical or as a mismatched set of poetic conceits.

In sonnet 110 Shakespeare, as the Poet, recalls the process he went

through to discover the living philosophy present in his ‘breast’ (110.14).

‘Tis true’, he says, he went here and there expressing a ‘motley’ of ‘views’

(110.2). He ignored his inner ‘thoughts’ for the ‘views’ of others. He turned

his ‘new affections’ into the typical ‘offences’ of ‘old’ (110.4). He looked on

‘truth askance and strangely’ (110.6).

When ‘truth’ (‘the endless jar’ between ‘right and wrong’) is used

logically, it is the process of ‘thought’, ‘essays’, or the sharing of ‘views’,

which enables the Poet to assess the nature of the ‘old offences’. These

‘blenches’ or testing enquiries, gave his ‘heart an other youth’ (110.7). It led

him to the ‘proof ’ that youth is the source and driving force of ‘love’ (110.8).

The Sonnet dynamic, from nature, through increase, to truth and beauty, is

the basis for a sound philosophy of love.

‘Now’, because the Poet has matured, ‘all is done’ (110.9). He has no

need to ‘grind’ his ‘appetite’ on ‘newer proof ’ (110.11). He will no longer

‘try an older friend’, or youth, whom he considers the true ‘God in love’

(110.12). Youth confines his expectations. His going ‘here and there’ has

led him back to the ‘pure and most most loving breast’ of nature.

In the couplet, the Poet has found his ‘heaven’ on earth and, as he values

his youth, he welcomes it as his next ‘best’. Not appreciating Shakespeare’s

profound logic with its critique of traditional beliefs, most editors remove

the capital G from ‘God’.

Sonnet 111

O for my sake do you wish fortune chide,

The guilty goddess of my harmful deeds,

That did not better for my life provide,

Than public means which public manners breeds.

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

And almost thence my nature is subdued

To what it works in, like the Dyer's hand,

Pity me then, and wish I were renewed,

Whilst like a willing patient I will drink,

Potions of Eisel 'gainst my strong infection,

No bitterness that I will bitter think,

Nor double penance to correct correction.

Pity me then dear friend, and I assure ye,

Even that your pity is enough to cure me.

In Shakespeare’s philosophy, Nature the sovereign mistress incorporates all

possibilities, good and evil, true and false, right and wrong. The Mistress,

as the representative of the human female, derives directly from nature, and

so embodies all human possibilities. As the Mistress is the source of beauty

(seeing) and truth (saying), she both senses or sees the natural relation

between what is best and what is worst (sonnet 137), and is able to articulate

or say what is true and what is false.

The Master Mistress or youth is the male possibility derived from the

Mistress. The youth needs to recover the natural logic of truth and beauty

in their relation to the potential for increase in nature. The youth’s existence

and his understanding are determined by the logical requirement to return

to the Mistress for the perpetuation of humankind. If he does not perpetuate

himself, he will be reabsorbed into nature without issue.

In sonnet 111 the Poet asks the youth if he ‘wishes’ to ‘chide’ the ‘guilty

goddess of my harmful deeds’ (111.2). The ‘guilty goddess’ represents the

aspect of nature that corresponds to the Mistress. In sonnet 110 the Poet

had lamented selling himself cheaply to the false views that led him to

devalue the importance of youth in the persistence of life. He now questions

whether the Mistress can be blamed for his succumbing to ‘public means’

and ‘public manners’ (111.4). When public beliefs and morals are contrary

to natural logic such a view ‘breeds’ a situation that does not ‘better’ provide

for the Poet’s ‘life’. The ‘goddess’ cannot be blamed for the ‘harmful deeds’

if the idealism that drives the deeds falsifies the justice of her natural love.

Because the Poet had once ignored natural logic he accepts that ‘my

name receives a brand’ (111.5), or mark of guilt. He can no more escape

nature than a Dyer’s hand escape the dye in which ‘it works’ (111.7). The

Poet has learnt to subdue his ‘nature’ to act in accord with nature. He asks

for the youth’s ‘pity’ so that his own energy can be ‘renewed’. He is willing

to accept the necessary remedy, or ‘potions of Eisel’, to cure his ‘strong

infection’ (111.10). Nothing would be too ‘bitter’ to cure the ‘bitterness’ of

his guilt. He will do ‘double penance to correct correction’ (111.12) because

traditional religious penance leads to a false reverence for false views.

In the couplet the Poet appeals to the pity of youth to sustain him in

youth’s true purpose. Such friendly pity would be ‘enough to cure me’.

Editors change ‘wish’ (111.1) to ‘with’ because they do not understand the

logic of the set. They perpetrate the guilt associated with natural events for

which Shakespeare provides the logical remedy.

Sonnet 112

Your love and pity doth th'impression fill,

Which vulgar scandal stamped upon my brow,

For what care I who calls me well or ill,

So you o'er-greene my bad, my good allow?

You are my All the world, and I must strive,

To know my shames and praises from your tongue,

None else to me, nor I to none alive

That my steeled sense or changes right or wrong,

In so profound Abysm I throw all care

Of others voices, that my Adder's sense,

To critic and to flatterer stopped are:

Mark how with my neglect I do dispense.

You are so strongly in my purpose bred,

That all the world besides me thinks y'are dead.

Sonnet 112 hints at the transformation some sonnets written in the 1590s

may have undergone as Shakespeare modified and then welded them

together as an expression of his philosophy by 1609. In its final form, the

theme of 112 follows directly on from 110 and 111. The Poet rectifies his

past ‘neglect’ by accepting the life potential of youth.

But there are also hints in sonnet 112 of the offence given Shakespeare

in 1592 when Robert Greene called him an ‘upstart crow’. The offence

seems to be alluded to with the mention of ‘vulgar scandal’ (112.2) and ‘o’ergreene’

(112.3). If the original sonnet was written to rebut Greene, its

revision to convey the Sonnet philosophy now supersedes the original

purpose. The present form of the sonnet does not make sense as an account

of Shakespeare’s response because Greene was on his deathbed in 1592. The

meaning of o’er-greene has been given an ironical twist to convey the

recovery of the Poet’s love for the potential of youth.

The youth o’er-greenes or over-grows the void left by the ‘bad’ views

attributed to the Poet so that his ‘good’ views will thrive (112.4). The Poet’s

appreciation of the dynamic of truth, or ‘well or ill’, is reconnected to the

life force of youth. The youth, representing the male sexual dynamic in nature, is ‘my All the world’

(note the capital A). The Poet will ‘strive to know’ his ‘shames and praises’

from the youth’s ‘tongue’ (112.6). The pun on ‘tongue’, as both language

and sexual organ, connects the logic of truth with the sexual processes of

life. Consequently, the Poet’s ‘steeled sense’, or the old views engraved on

his ‘brow’, give way to his revived capacity to judge ‘right or wrong’ (112.8).

The Poet ‘dispenses’ with his previous ‘neglect’ by throwing into the

‘Abysm’(112.9) those other ‘voices’ or views. His ‘Adder’s sense’, or hearing,

is no longer impressed by them. As the change in the meaning of ‘o’ergreene’

bears out, he has ‘stopped’ caring about misdirected criticism and

flattery (112.11).

In the couplet, because the Poet and youth are related through increase,

they are both strongly ‘bred’ for the same ‘purpose’. While the Poet has

recovered his love of life, the old ‘all the world’ view (note the small ‘a’) still

‘thinks’ in terms of a ‘dead’ youth. Editors who emend ‘y’are’ (112.14) to

‘th’are’ reveal their ignorance of Shakespeare’s natural logic.

Sonnet 113

Since I left you, mine eye is in my mind,

And that which governs me to go about,

Doth part his function, and is partly blind,

Seems seeing, but effectually is out:

For it no form delivers to the heart

Of bird, of flower, or shape which it doth lack,

Of his quick objects hath the mind no part,

Nor his own vision holds what it doth catch:

For if it see the rudest or gentlest sight,

The most sweet-savour or deformed'st creature,

The mountain, or the sea, the day, or night:

The Crow, or Dove, it shapes them to your feature.

Incapable of more replete, with you,

My most true mind thus maketh mine untrue.

Sonnets 113 and 114 are connected logically by ‘or’. Because of their significance,

though, they warrant separate treatment. Sonnet 113 particularly

needs to be considered closely because it has two of the more illogical

emendations in the set. The change from ‘lack’ (113.6) to ‘latch’ to make

the rhyme prefect when there are a number of imperfect rhymes throughout

the Sonnets, and interference by most editors with the last line, reveals a

misunderstanding of the logic of the two sonnets.

To appreciate the meaning of sonnet 113 it should be remembered the

Master Mistress represents both a young male and the youthful Poet. So

when the Poet says he ‘left’ the youth, he refers to the relation of youth to

maturity. ‘Mine eye’, or the true eye of the Poet’s youthful ‘vision’, is in his

‘mind’ (113.1) because the potential of youth ‘governs’ his mature mind

(with a sexual pun on eye). Because of the influence of the ‘eye’ of youth,

the Poet’s ‘seeing’ is ‘partly governed’ by his vision of objects in the world,

but is ‘partly blind’ (113.3). His ability to ‘see’ is ‘effectually out’ because of

the logical influence of the sexual potential of youth (113.4).

The aging Poet’s ‘seeing’ eye no longer delivers ‘forms to his heart’

(113.5). His heart ‘doth lack’ shapes of ‘birds, flowers, and quick objects’

(113.7). It no longer ‘catches’ shapes with the ‘vision’ (113.8) he had when

young. The ‘mind’s eye’ of youth, housed deep in the Poet’s mind, ‘shapes’

all the ‘sights’ it sees to the ‘features’ of the youth (113.12).

‘No form’ or ‘vision’ from the retina reaches the aging Poet’s heart

because his heart responds only to the life potential of youth. Because his

mind ‘doth lack’ shapes it cannot deliver them to the heart. The change from

‘lack’ to ‘latch’ contradicts the sonnet’s meaning because it implies the mind

and heart ‘latch’ on to the objects of sight. The part rhyme lack/catch

correctly conveys the intent of Shakespeare’s philosophy.

In the couplet, love fills the Poet’s heart. ‘Incapable of more’ he is ‘replete’

with the love of life rising out of nature through the sexual dynamic, the

increase potential, and the dynamic of truth and beauty. The legacy of youth,

or the ‘most true mind’ of human persistence, makes the aging Poet’s postsexual

perception of the world effectually ‘untrue’.

Sonnet 113 addresses the tendency of age to accept false views, as

discussed in sonnets 110 to 112. Most editors, having changed ‘lack’ to ‘latch’

because they do not appreciate Shakespeare’s philosophy, then feel compelled to

change the meaning of the final line. They alter the last three words in

various ways in an attempt to make them conform to the prejudice of their

views.

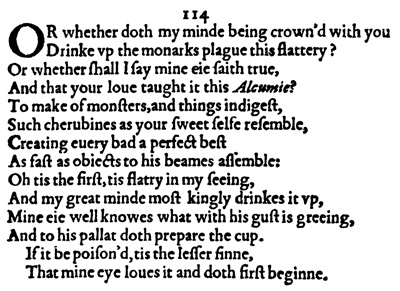

Sonnet 114

Or whether doth my mind being crown'd with you

Drink up the monarch's plague this flattery?

Or whether shall I say mine eye saith true,

And that your love taught it this Alchemy?

To make of monsters, and things indigest,

Such cherubins as your sweet self resemble,

Creating every bad a perfect best

As fast as objects to his beams assemble:

Oh 'tis the first, 'tis flatt'ry in my seeing,

And my great mind most kingly drinks it up,

Mine eie well knows what with his gust is greeing,

And to his palate doth prepare the cup.

If it be poisoned, 'tis the lesser sin,

That mine eye loves it and doth first begin.

Sonnet 114 continues the exploration of the effect of youth on the Poet’s

eyes, mind, and heart. In sonnet 113 the Poet’s natural vision from ‘mine

eye’ entered his mind allowing him to appreciate the logical relation between

youth and age. (The relationship was captured in the ‘eye I eyed’ of sonnet

104.) Sonnet 14 set the stage for the combination of mind and eyes when

it stated, ‘from thine eyes my knowledge I derive’. As the final increase

sonnet, it forged the eye-to-eye connection between increase and the mind.

The first quatrain presents two possibilities. The first ‘Or’ (114.1) recalls

sonnet 113 where the potential of youth governs the Poet’s mind from

within his heart. The Poet asks, does ‘my mind’, being ‘crowned’ with the

potency of youth to create ‘my most true mind’ (113.14), allow it to ‘drink

up’ the seeming irony of a ‘monarch’s plague’ of flattery (114.2)? With the

second ‘Or’ the Poet asks, ‘shall I say mine eye saith true’ (114.3) when he

recalls that the influence of youth’s idealising tendency ‘taught it this

Alchemy?’

The Poet is aware that such schooled idealism converts ‘monsters’ and

‘indigestible things’ (114.5) into innocent cherubins. Such ideal love falsely

makes ‘every bad a perfect best’ (114.7) of the objects that assemble in the

eye’s ‘beams’ (114.8). In sonnet 14, the Poet has rejected the influence of

such fanciful astrology in favour the natural logic of understanding, eye to

eye.

So, the youth’s potential for life in all its variety of the first two lines is

contrasted with youth’s tendency to idealise life in lines 3 to 8. For the Poet

there is no doubt which is ‘first’ (114.9). His sense of being replete in sonnet

113 allows him to accept the crowning of his ‘great mind’ (114.10), or the

combination of youth with maturity. He ‘most kingly drinks up’ the ‘flattery’

due to him by acknowledging the youth within. Despite his diversion into

the ideal in lines 3 to 8, the Poet’s eye ‘well knows’ what he is agreeing to

(114.11). He prepares to drink from the ‘cup’ (114.12) to celebrate his

connection to natural logic.

In the couplet the Poet stands firm. If the cup is poisoned (with the

‘flattery’ of always being imbued with youth) it is the ‘lesser sin’ because

whatever way he decides, nature has the last say. His ‘eye’ will always love

the first option and obey the natural logic of a ‘first beginning’ or increase.

The couplet of sonnet 115 increases the crescendo of the sonnet logic when

it identifies love as a ‘Babe’ that gives ‘full growth to that which still doth

grow’.

Sonnet 115

Those lines that I before have writ do lie,

Even those that said I could not love you dearer,

Yet then my judgment knew no reason why,

My most full flame should afterwards burn clearer.

But reckoning time, whose millioned accidents

Creep in twixt vows, and change decrees of Kings,

Tan sacred beauty, blunt the sharp'st intents,

Divert strong minds to th'course of alt'ring things:

Alas why fearing of time's tyranny,

Might I not then say now I love you best,

When I was certain o'er in-certainty,

Crowning the present, doubting of the rest:

Love is a Babe, then might I not say so

To give full growth to that which still doth grow.

The 126 sonnets to the Master Mistress address the conditions an idealistic

youth must meet to achieve a mature relationship with the Mistress, and so

with Nature, the sovereign mistress (126.5). Every sonnet carries the imprint

of this larger purpose. From the increase argument of the first 14 sonnets,

through the transitional the increase to poetry sonnets (15 to 19), to the

detailed analysis of truth and beauty from sonnet 20, the Poet addresses the

tendency for male idealism to assume priority over the female or nature.

In sonnet 115, nearing the end of the youth sequence, the Poet compares

the excessive idealism of youth with the natural logic of his mature

worldview. The first quatrain recalls the ‘motley of views’ reviewed in

sonnets 110 to 114. The Poet admits that the ‘lines’ he once wrote did ‘lie’.

He lied ‘even’ when he said he ‘could not love’ the idealised youth ‘dearer’

(115.2). His love has become dearer because what seemed then to be his

‘most full flame’ now burns ‘clearer’ (115.4). His immature idealistic

‘judgment’ could not provide a ‘reason why’ his mature love or ‘most full flame’,

when aligned with the logic of nature and increase, should ‘burn clearer’.

It took ‘time’ to achieve his mature ‘reckoning’ (115.5). Time with its

‘millioned accidents’, or millions of natural surprises down generations, has

‘crept between vows’ (including Anne Hathaway’s pre-nuptial conception

of their own child), changed the ‘decrees of Kings’ (as in the history plays),

tanned the raw hide of ‘sacred beauty’, and blunted the ‘sharpest intents’.

Given time, ‘strong or stubborn minds’ can be diverted to the natural

‘course’ of the way ‘things alter’ (115.8). ‘Alas’ then, why did the Poet once

fear ‘time’s tyranny’ at death, when all along his natural mind knew increase

was the logical basis for love. He can now say he ‘loves youth the best’

because he has gained certainty over ‘incertainty’ by ‘crowning the present’

and casting ‘doubt’ over the ‘rest’ (115.12), or his former adolescent views.

In the couplet, the Poet appreciates that ‘love is a Babe’ and, against

uncertainty, he has every right to ‘say so’. Such a love gives ‘full growth to

that which still doth grow’, or acknowledges the process of human

persistence. Commentators who deny the influence of the increase theme

past the first 19 sonnets typically talk of Shakespeare’s ‘un-Platonic

hyperbole’ to account for such phrases as ‘millioned accidents’. Because they

are blind to its natural meaning, they presume he was indulging exaggeration

for effect. Ironically, Shakespeare anticipates the ‘motley of views’ to

which the Sonnets are still subjected.

Sonnet 116

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments, love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no, it is an ever fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand'ring bark,

Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.

Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle's compass come,

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom:

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

Sonnet 116 is often read at marriage services in the belief it celebrates the

ideals of married love. But its particular beauty derives from its relocation

of idealised male-based love within the deeper current of natural love. The

two possibilities find their correct place within the Sonnet philosophy. The

Poet, who has already realigned the feminine and masculine aspects of his

mind, offers to assist the youth move beyond an over-dependency on the

male ideal. He would reconcile the youth’s male-based idealism and his

female roots so together they can experience ‘the marriage of true minds’.

Once the Sonnets are appreciated as a coherent set, whose natural

philosophy reconciles opposing tendencies in the mind, then ‘the marriage

of true minds’ clearly expresses the intent to metaphorically ‘marry’ the

minds of the mature Poet and the idealistic youth (or both poles of the Poet’s

own mind). The Poet will not ‘admit impediments’ (116.2) to reforming

the youth’s mind so they can meet in a ‘true’ relation of body and mind. In

sonnet 115 the Poet, given ‘time’, would convert ‘strong’ or stubborn minds

to the natural ‘course of things that alter’. To the same end in sonnet 116

he warns that ‘love is not love’ if it only ‘alters’ for the sake of ‘alteration’

or ‘bends’ with those who would ‘remove’ (116.4) it from its natural course.

Instead, love ‘is an ever fixed mark’ (116.5) that is not ‘shaken’ or fearful

of ‘looking on tempests’. The ‘looking’, or the use of the eyes, sees the ‘star’

that guides ‘every wandering bark’ even though, sexually and erotically, it’s

‘worth’ or potential is ‘unknown’ at the time ‘his height be taken’ (116.8).

Sonnet 14 recognised ‘thine eyes’ as the ‘constant stars’ and the priority of

the body over the mind. The loving relation between the ‘wandering’ sexual

eye and the mind’s erotic eye ‘marries’ body and mind.

The erotic imagery intensifies in the third quatrain. ‘Love is not Time’s

(death’s) fool’ (116.9), because human life continues through increase despite

death. So love can playfully allow time’s ‘bending sickle’ to ‘come’ close

within the ‘compass’ of its ‘rosy lips and cheeks’. Love can be cheeky because

it ‘alters not’ with time’s ‘brief hours and weeks’ but persists ‘even to the

‘edge of doom’. The last line of sonnet 14 stated that ‘doom’ threatens only

if human beings do not increase.

In the couplet, the Poet stakes his whole philosophy on his natural understanding

of love. If he is in ‘error’ and his error is ‘proved’, then ‘no man

ever loved’. Without increase there can be no ‘love’, and the Poet could not

have ‘writ’ his sonnets. Sonnet 116 has a singular beauty, not because it

celebrates ideal love, but because it expresses in the form of a poetic vow

the logical conditions for deep and abiding love in the natural course of life.

Sonnet 117

Accuse me thus, that I have scanted all,

Wherein I should your great deserts repay,

Forgot upon your dearest love to call,

Whereto all bonds do tie me day by day,

That I have frequent been with unknown minds,

And given to time your own dear purchased right,

That I have hoisted sail to all the winds

Which should transport me farthest from your sight.

Book both my willfulness and errors down,

And on just proof surmise, accumulate,

Bring me within the level of your frown,

But shoot not at me in your wakened hate:

Since my appeal says I did strive to prove

The constancy and virtue of your love.

Sonnet 116 ended with an uncompromising challenge from the Poet. If it

could be proved he was in ‘error’ in his understanding of the nature of love,

then ‘no man ever loved’ and he never wrote a word. Sonnet 117 renews

the challenge. The Poet asks the youth to accuse him of just such an error.

First, that he has ‘scanted all’ or neglected the love of everything and

everyone, from ‘wherein’ he would ‘repay’ the ‘great deserts’ or natural

qualities of the youth (117.2). Second, that he ‘forgot’ to ‘call upon’ or evoke

the ‘dearest love’ inherent in youth, from ‘whereto he is bound ‘day by day’

(117.4) in the everyday processes of nature.

Furthermore, the youth should accuse the Poet of frequenting

‘unknown’or unworthy ‘minds’ (117.5). Or that he has sold ‘to time’ (death)

the youth’s ‘own dear purchased right’ or costly idealised love (critiqued in

sonnet 31). The ‘dearest love’ (117.3) becomes the ‘dear purchased right’

(117.6) as the Poet plays on the two meanings of ‘dear’. Or he could be

accused of avoiding the implications of youth by ‘hoisting sail to all the

winds’ to ‘transport’ himself ‘farthest’ from youth’s ‘sight’ (117.8). By scanting

or ignoring the natural love of life he would put himself out of ‘sight’, or

beyond the eye-to-eye relation that is the basis for determining truth and

beauty.

But the Poet, since his youth, had been determined to discover the

logical relation of truth and beauty. Any ‘wilfulness and errors’ he made

could be booked down (117.9) and on ‘just proof ’ he would be rightly

levelled by the youth’s ‘frown’ or judgment (117.10). But his trial and error

toward a mature understanding of the logic of truth and beauty is intended

as a model for the youth, even though the youth mistakes the Poet’s method

for a fault and shoots at him in youth’s ‘wakened hate’ (117.12). To break

youth’s excessive dependency on the ideal the Poet sets himself up as a target

the better to reveal the logical relation of love and hate.

In the couplet, the Poet’s ‘appeal says’ he ‘did strive to prove the

constancy and virtue’ of the youth’s natural ‘love’. His ‘proof ’ is based on

the logic of ‘love’ evident in nature and its perpetual processes. By reconciling

his sense of love with his ‘day by day’ (117.4) existence down generations

the youth can connect with the logic that makes sense of both his

idealised ‘love’ and his ‘wakened hate’ toward the Poet. The alternative is to

enter the cycle of idealist prejudice that transfers hate to others as it claims

all love for itself. This was basis of the conflict Shakespeare most likely

witnessed between the religious sects of his day.

Back to Top

Roger Peters Copyright © 2005

Introduction

1-9

10-21

22-33

34-45

46-57

58-69

70-81

82-93

94-105

106-117

118-129

130-141

142-153

154

Emendations

|