Roger Peters Copyright © 2005

JAQUES

INQUEST

QUIETUS

ACQUITTAS

The Quaternary Investigation into the Evolution Toward the Uniqueness in Shakespeare

The relationship of Shakespeare's philosophy to the American Declaration of Independence & the American Constitution

Thomas Jefferson’s reference to the ‘Laws of Nature’ and to ‘Nature’s God’

in the first few lines of the Declaration of Independence (1776) and his insistence

on the religious and political freedoms guaranteed by the First

Amendment to the American Constitution (1791) ensured that pluralism

became the founding credo of the United States. Yet, despite the widespread

recognition of Jefferson as the spiritual father of the United States, the philosophic

basis of his framework for tolerance has not advanced much beyond

its original enigmatic expression.

These notes will suggest that the philosophy of Shakespeare’s Sonnets of 1609 not only provides a sound logical base for Jefferson’s pluralism, but that Shakespeare’s application of the philosophy in the social/political dynamic of his 40 plays and longer poems provides an opportunity to enrich the pluralistic dynamic. The notes will concentrate on correspondences between

the Sonnet philosophy and the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.As Thomas Jefferson was responsible for the wording of the Declaration, it will discuss his understanding of the relation of nature and God and his campaign to separate Church and State.

So the logical structure of the Sonnets will be compared with the political

structure heralded in the Declaration and legitimated in the Constitution. Then the mythic logic of the Sonnets will be used to identify elements in the

Declaration that could elevate it from being an abstract framework, with little

other than legislative definition in the American Constitution, to a wellspring

for an inclusive mythic logic based in nature.

Shakespeare's natural philosophy of 1609

These four volumes demonstrate that in the period in which the New World

was discovered and colonised Shakespeare was formulating a philosophy in

his Sonnets of 1609 that set out to critique and correct the traditional attitude

toward biblical mythology. In particular he restores the logical priority of

nature over mythology and the priority of the female over the male. And

in each of his plays and longer poems he demonstrates how to generate a

mythic expression consistent with the natural logic articulated in the Sonnets.

Although the four volumes are the first in 400 years of scholarship to

present the Sonnet philosophy, many students of Shakespeare have recognised

that his plays and poems are based primarily in nature, rather than in biblical

mythology. Ironically, though, while commentators admit that Shakespeare’s

plays show no evidence of an adherence to traditional beliefs, many feel duty

bound to suggest he was at least a closet believer (if only in support of his

status as England’s national poet).

But both Shakespeare in his Sonnet philosophy and Jefferson in the

Declaration and Constitution wanted to move beyond the biblical politics of

a pre-global Euro-centric world. The plurality of the Sonnet philosophy,

which derives the logic of mythic expression from the dynamic of the natural

world, anticipated the advance toward plural global politics heralded in the

Declaration and guaranteed by the Constitution. This is despite the fact that

Jefferson, even though he would have been aware of the general regard for

nature in the works of Shakespeare, was ignorant of the precisely formulated

philosophy of the Sonnets.

In Jefferson’s day the biblical paradigm was fast collapsing as a credible world-view under the philosophical critique of thinkers such as Spinoza, Locke, and Hume. Added to the logical attack was the theoretical critique

by social/political/scientific thinkers of the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries. Their concern for the consequences of allowing a religion to be

instrumental in the politics of a state inspired a new attitude of secularisation

when the American colonies asserted independence from their European

forbears. The memory of Christian intolerance and even atrocities in Britain,

Europe and the Americas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and

the awareness, by those who wrote the Declaration and Constitution, of a new political order emerging in eighteenth century France created an opportunity

to institute a less irrational society.

The philosophy in the Sonnets

As this is one of a series of short essays to be incorporated in the four

volumes that detail Shakespeare’s philosophy, no more than an outline of

the basic elements of his natural logic will be given. It is sufficient to

remember that the Sonnet philosophy acknowledges the priority of nature

over the sexual dynamic, and that the sexual dynamic entails the logical

requirement for humans to increase if they wish perpetuate themselves.

Then, once the logic of the increase dynamic within nature is acknowledged,

it follows that the possibility of increase is prior to the dynamic of

understanding or truth and beauty

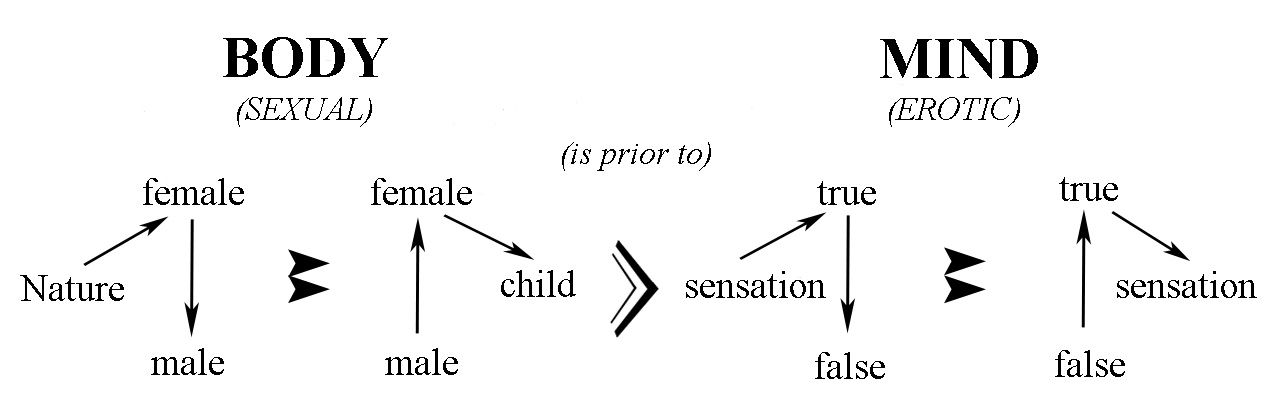

The relationships of the major elements of the Sonnet philosophy are represented diagrammatically in the Nature template.

Nature Template

The linear arrangement of the elements captures the logical entailment beginning with nature as the given, through to the sexual dynamic and the dynamic of sensations and language. The word ‘beauty’ on the right represents all sensations in the mind including idealised thoughts such the absolute

as God. In the Sonnet logic, nature is the possibility that encompasses all

else, while the ideal as God is consequential on the development of the

human mind in nature.

The Sonnets are unique in the way they reflexively lay out the natural logic of life. As well as articulating natural logic they simultaneously acknowledge their dependence as an expression on the priority of the body

over the mind. Shakespeare’s plays and longer poems have an unmatched

veracity and felicity because they are based in a philosophy that recognises

the sexual dynamic of human increase out of nature is prior to the erotic

dynamic of the desires of the mind. Writing that expresses the logic of the

priority of nature and the sexual dynamic over the inherent eroticism of

human understanding is potentially mythic.

The inverted logic of the Bible

Genesis, as a book begun around the time of the transition from oral to

scribal culture, seems, in the eroticism of the relations between God and

mankind, to acknowledge the logical limitations of the written word. Genesis

recognises the erotic logic of the act of writing in that writing is logically

distinct from the biology of the sexual act. While the complete inversion of

the natural order in the mythology of Genesis suggests it was originally written

to acknowledge the priority of life over art or the sexual over the erotic, at

some point in the history of the Hebrew culture the erotic mythology of

Genesis was given priority over the sexual relationships in nature.

The reduction of the anti-nature male-based dynamic in Genesis to a

religious dogma, enforced as fact by Hebrew and Christian culture, inverts

for social, political and personal expediency, the natural priorities of life and

art. Because the myth of Genesis is so erotic in its complete inversion of

sexual logic, the doctrinaire belief in Genesis as fact has meant the religions

based on the priority of the male God have become bastions of their own

irredeemable irony.

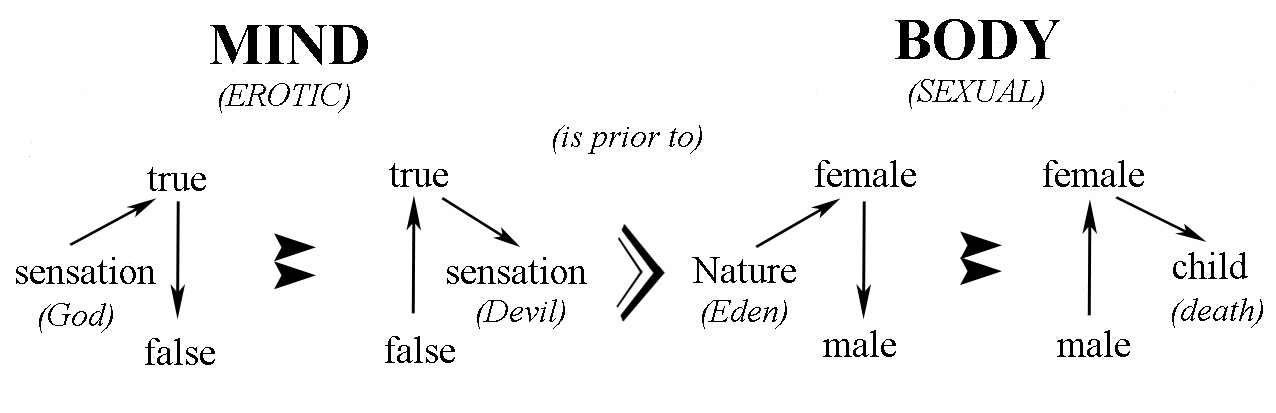

When the order of events dictated by religious prerogatives is substituted

in the template for natural logic, the result is riddled with inconsistencies

and contradictions (as noted by the philosophers of the Enlightenment).

God template

Whereas in the template for natural logic the priorities follow consistently

from left to right, it is not possible to represent the biblical priorities consistently.

The God template can only attempt to indicate the consequences of

inverting natural logic because the dogmas of faith can be represented only

crudely. Some of the familiar inconsistencies are the priority given to the

erotic God of the mind over nature, the unnatural priority of male over

female, the confounding of false and true so that evil supplants good, and the

life-defying connection of procreation or birth with the finality of death.

The book of Genesis expresses the mythological awareness of the

Hebrew peoples, and provides the mythological basis for the other books

of the Hebrew Bible. It is not until the New Testament that the erotic logic

of myth is again asserted. The Christian Bible both acknowledges the

mythological dynamic of Genesis but, as the founding myth for a new

religion, expresses the eroticism of Genesis in terms of Jesus Christ. The

eroticism of such doctrines as the Immaculate Conception, the virgin birth,

Christ’s death and resurrection without offspring, and the promise of a nonsexual

heaven, are key indicators that a new religious myth has been

invented. And as with the myth of Genesis, believers in the New Testament

accepted the erotic logic of the myth as fact, so perpetuating the inversion

of the sexual and the erotic in their minds.

Biblical myths, old and new, commit the logical sin of accepting as fact

their own erotic desires. The lack of irony or any form of humour in the

Bible, compared with the pervasive irony and humour in Shakespeare, is a

sure indication of the intent to deceive. Shakespeare demonstrates in all his

plays that the illusions created through language are useful fictions that need

the irony of awareness to ensure they remain useful fictions.

Shakespeare shows in his 154 sonnets, 38 plays and 4 longer poems, how

to create a multiplicity of expressive possibilities with the correct logical

consistency at the mythic level from the basic elements of natural logic.

Because his philosophy is consistent and coherent, his critique in the Sonnets

of over-idealised expectations and his critique in the plays of the tyranny of

the ideal provide the appropriate methodologies for operating in a society

with pluralistic expectations.

The Declaration of Independence

When the relevant statements of the Declaration of Independence and the

American Constitution are compared with the logic of the Sonnets, there is

a correspondence that might be expected if the Declaration was a rejection

of the social/political dynamic of the old world. Thomas Jefferson in

particular was determined to institute a society in which religious dogma

could not play a part in the politics of the State. For Jefferson, the idea of

a religion having a role in government was a violation of the intent

of ‘Nature’s God’. As a deist he believed that God the creator was

immanent in nature so all one had to do was to act in conformity with

the Laws of Nature.

In the first few lines of the Declaration, the rejection of the theistic belief in

a God who actively intervenes in the world in favour of a deistic God who

creates the natural world and whose intent is evident in natural law is given

precise expression. Jefferson reflects the shift in sensibility by mentioning the

word ‘Nature’ twice before he mentions ‘God’. To emphasise his belief that

the creator’s work is evident in nature, the phrase ‘Laws of Nature’ precedes

‘Nature’s God’ (just as the word ‘Nature’ precedes ‘God’). For deists it is not

possible to know God or the creator of the world otherwise.

When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people

to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another,

and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal

station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a

decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should

declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these

truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are

endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that

among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. (1)

Deists like Jefferson believed that once God created the world he did

not intervene in its progress and destiny. All ‘men’ were created equal and

endowed with ‘unalienable Rights’. Even though, like most of his contemporaries,

Jefferson understood the world in pre-Darwinian terms (he

believed in the immutability of species, even hoping to find living examples

of old world fossils in the American West or elsewhere) he intuitively grasped

the Darwinian logic that mind-based rights were derived from nature.

Jefferson (and his colleagues) were determined to reject a society based

on a belief in a theistic God, who could be petitioned for favours and who

made his intentions known through personal revelation. Their experience

was that the theistic basis of Judeo/Christian belief led inevitably to a proliferation

of feuding sects and to the persecution of atheism, its logical

counterpart.

Because the attributes of theism and atheism are psychological attributes

from within the human mind, like gnosticism and agnosticism, they are

perpetually opposed. The pluralistic advantage of Jefferson’s adherence to

deist logic is apparent in the illogic of coining words like adeistic or anature.

The soundness of his philosophic insight into the distinction between the

natural logic of deism and the psychology of theism provides the logical

precondition for a pluralistic society.

The formulators of the Declaration wished to remove themselves from

all they considered iniquitous and injurious in the English unification of

Church, Crown and parliament. Because the sectarian injustice and violence

in the old world was seen as a direct consequence of the Church as an arm

of the State, Jefferson and his colleagues wished to subscribe directly to the

laws of the natural world, which lack the absolute evil of Christian schism

and retribution. So in their desire to emphasise the implications of their

insight into natural logic, the Declaration appealed to ‘Nature’s God’.

So it is not surprising that the First Amendment to the Constitution

reinforces the Declaration’s emphasis on nature by forbidding Church

involvement in the running of the State. The appeal to the Laws of Nature

has a logical significance for the establishment of the State. The pluralism

inherent in Jefferson’s deism through Nature meant that logically he was

one step away from demoting God the creator to his correct place in

natural logic.

Unbeknown to Jefferson the move had been made by Shakespeare 200

years earlier in the natural logic of the Sonnets. The first few lines of the

Declaration, which prioritise nature over God in human affairs, point in the

direction of the Sonnet logic. The significance of nature in the plays and

poems of Shakespeare finds a resonance in a New World that wished to put

behind it the worst effects of unbridled idealism, as they showed themselves

in the Reformation and Puritan excesses in England and Europe.

The intent of the Declaration, though, (as in the works of Shakespeare)

was not to deny the importance of the psychology of belief for individual

citizens. Hence, in keeping with the relationship of nature and God, the

writers of the Declaration talk of the ‘Creator’ providing for individual human

hopes and aspirations by guaranteeing ‘certain unalienable Rights, that

among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness’. And the First

Amendment of the Constitution was enacted in part to protect those who

resorted to the psychology of theistic belief.

The reference to ‘Nature’s God’ is the one mention of God by name in

the Declaration. The only other allusion to a deity in the lives of ‘men’ is at

the conclusion where ‘the Supreme Judge of the World’ is invoked to ensure

the ‘rectitude of our intentions’. Again the Supreme Judge is evident through

Natural Laws and Rights. Significantly, against Jefferson’s vehement

objection, Congress then added the words ‘with a firm reliance on the

protection of divine Providence’ to the Declaration. Jefferson retained his own

version, which he would show in protest.

Jefferson and his colleagues quarantined the iniquities in religious dogma

by subjecting the beliefs based in the God of the Bible to the Laws of Nature.

The plurality of the young American nation was guaranteed by relocating

the male Gods of idealistic theisms within the laws of Mother Nature.

Jefferson had correctly identified the removal of the male Gods of the Bible

to their appropriate place in nature’s logic as the primary logical requirement

for a nation to exist in harmony and justice. (The wording in the Declaration

recalls Shakespeare’s critique of the idealising Master Mistress in the Sonnets.

The male as Master Mistress, who is second to the female as Mistress, is

governed by nature as the sovereign mistress.)

The Constitution and the First Amendment

The Declaration’s determination to remove the theistic God from political

power is given direct expression in the Constitution. No mention is made of

the idea of God in the seven Articles of the Constitution or the ten

Amendments of the Bill of Rights. Instead, in the First Amendment in the

Bill of Rights, the logical divide between the State and the Church is stipulated.

The express intention is to forbid any one religion from becoming

the religion of the nation. As with the Declaration, though, the right for any

individual to exercise their psychological right to believe what they will is

defended, on condition that their religion is second to the logic of the State

based in nature.

Amendment 1

Freedom of religion, speech, and the press;

rights of assembly and petition

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of

religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the

freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably

to assemble, and to petition the government for redress of grievances.

A comment is added in the World Book from which the above text was

taken.

Many countries have made one religion the established (official) church

and supported it with government funds. This amendment forbids

Congress to set up or in any way provide for an established

church. It has been interpreted to forbid government endorsement

of, or aid to, religious doctrines. Congress may not pass any laws

limiting worship, speech, or the press, or preventing people from

meeting peacefully. (1)

The Declaration of Independence and the Articles and Amendments of the

American Constitution create a nation in which no religion can become the

established power of the State but in which all religions have freedom of

expression and assembly. The obvious intention and effect is that if any

religion (all the major religions prioritise the male God over the female) were

to assume control, the consequence would be a return to intolerance and

so to sectarian bloodletting.

Of immediate interest then is the logical status of the structure or framework

provided for by the Constitution, which has successfully contained the

sectarian tendencies of the multitude of religious denominations active in the

United States of America. The issue is a profound one for a country whose

citizens frequently voice their belief in a male God, even when the belief

leads to bizarre expressions of self-interest. It is not uncommon for Americans

to thank their God for small miracles but excuse him the responsibility of

overwhelming disasters, natural or man-made. And, despite the injunction

of the First Amendment, theistic practices, such as prayers in schools and in

Congress, have accrued political sanction in American public life.

What, then, is the logic of the structure of the Constitution that guarantees

a peaceful co-existence in a veritable Babel of beliefs. If the intent of Jefferson

and others was to base their nation in the Laws of Nature, a philosophy is

required to articulate the natural logic of their hopes at the mythic level.

Beyond singular mythologies to Shakespeare’s mythic logic

Other than for the philosophy of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, there is no philosophic

system based in nature with the appropriate logical structure that

fulfils the pluralistic expectations of the Constitution. All other philosophies

in some measure explicitly or tacitly conform to the idealistic programme

of the Judeo/Christian paradigm or, having rejected the illogicality of such

beliefs, espouse if not scepticism then at least pragmatism.

The Constitution as it stands is a very pragmatic document that outlines

the role of Congress, the Executive and the Judiciary. Other than for the

Declaration of Independence, and the First Amendment, it creates a bare

framework under which the various belief systems and moral attitudes of

the nation are then constrained to co-exist.

Somewhat ironically, the Declaration and Constitution are enshrined in

Philadelphia and Washington, effectively superseding the biblical Commandments

or the dogmas of the Churches. And Jefferson is regarded as the

political, poetic and spiritual father of the nation. Americans look to the

founding documents as if they were more than abstract principles even

though they might wish their own religious beliefs had priority.

If the acknowledgement of the logical relation of nature and God was

integral to the establishment of the nation, then the current level of religious

belief across the nation seems retrograde. But because the Declaration and

the Constitution do not elaborate on the pan-mythic intent to establish a

nation under the ‘Laws of Nature’, is not surprising that the populace seeks

psychological consolation in the old mythologies.

The continued belief by many Americans in the illogicality of biblical

transcendence has coincided with the absence of an expressive elaboration

of a logico/mythic basis for the Constitution. And the absence of a philosophic

paradigm capable of doing justice to the intent of the founding

documents and providing for the mythic needs of citizens has created a

vacuum in which constant public avowal in the old beliefs is required.

Compared with the retrograde persistence of biblical dogma within the

American culture, the interest in Shakespeare’s plays is growing exponentially.

Whereas once only a select few plays were acted irregularly, there is

now a virtual competition to stage or film every play, even those plays once

considered traditionally obscure or offensive to the old beliefs.

The growing recognition that the works of Shakespeare have a mythic

resonance for the modern spirit, suggests his works contain an understanding

that might develop the abstract guarantees of the Constitution into a

consistent expression of mythic logic. When it is realised that Shakespeare’s

Sonnets articulate the philosophy behind all his plays and longer poems, and

that the philosophy articulates the logical conditions for any mythic possibility,

the significance of the philosophy for the contemporary pluralistic

American society should be evident.

The mythic depth of Shakespeare’s plays has been acknowledged by a

number of commentators. The plays have frequently been compared with

the Bible for their profundity of insight into the psychology of the human

condition. Many commentators prefer the works of Shakespeare because

they lack the self-serving dogma of the male-based Bible. They are aware

that Shakespeare’s works, with their true to life characterisations, faithfully

represent the dynamic of life and art.

Until the discovery and elaboration of his Sonnet philosophy in these four

volumes, the relationship between the works of Shakespeare and the

Declaration of Independence and the Constitution has been restricted to the

allusions made to him or his works by thinkers such as Jefferson, Emerson,

and Thoreau. It is not surprising, though, that the efforts of the thinkers of

the American revolution created a framework that expressed a more

consistent attitude toward humankind’s place in nature, and simultaneously

enacted Articles and Amendments that forbade any religion, and particularly

the male-God based religions, from any association with the State. Since

the late 1700s, however, there has been no development of their insights

into the logic of life and the illogicality of male-based beliefs.

The tendency in American philosophy to look to nature for succour,

especially in the natural philosophy of Emerson or Thoreau, has been overly

romantic in its rejection of idealism. Shakespeare’s logic in contrast shows

precisely how to contextualise the romantic and idealist temperaments

within the mythic logic of life. But because commentators have gravitated

to either an idealist or romantic approach to myth, Shakespeare’s articulation

of the logical conditions for all human thought out of nature has remained

insuperably difficult for them to understand.

A pluralistic society in a pluralistic world

Jefferson gave physical expression to the disestablishment of theism when

he designed the University of Virginia. By insisting the University be funded

by the State, and by putting its library instead of a chapel at the centre of

the campus, he created the world’s first secular university.

And 200 years previously, Shakespeare and his colleagues had staged plays

across the Thames to escape religious intolerance. In all his plays Shakespeare

argues against the injustices that arise when the idealising tendency in

humankind overreaches the logic evident in nature. Each play begins with

a situation of gross psychological posturing and ends with the restoration

of philosophic balance. To demonstrate the applicability of his logic to a

complete social dynamic his characters range from kings and cardinals to

lovers and beggars, any of who is capable of destructive self-delusion.

Because Shakespeare’s plays and poems express a consistent mythic

philosophy, which specifically addresses the negative consequences for

individuals and societies that exhibit excessive religious idealism, they seem

purpose made for a society in which the intentions of the founding

documents are so often subsumed in an excessive faith in religious transcendence.

The Sonnet philosophy, and its practical exercise in 40 plays and

poems, provides a natural antidote to the psychological excesses of malebased

faith. As the most profound and extensive set of deliberations on the

logic of myth out of nature ever written, the plays give detail and colour

to Jefferson’s bare intention to ensure Church and State are separated for

the good of the State.

The present legislative status of the Constitution proscribes religious

hegemony so that the logical inconsistencies behind the mythological beliefs

of the Hebrews, the Christians, the Muslims, and others, are controlled to

ensure their peaceful co-existence within the State. But, because of the

headstrong tendency of theism to place itself above the Constitution, the

advantage of having a comprehensive mythic philosophy that provides an

overview of all mythic possibilities should be obvious.

The works of Shakespeare not only foreshadow the framework of the

Constitution as an abstract of the natural logic of life but, by recovering the

status of nature as logically female and the priority of the female over the

male, and by generating a consistent understanding of aesthetics and ethics,

they give added legitimacy to the Constitution, and enhance its philosophic

potential as a mythic recourse that can mitigate the psychological differences

in a society that accommodates competing beliefs.

Epilogue

The global world has not yet caught up with the pluralistic philosophy of

Shakespeare. But neither has it appreciated the mythic logic in the art of

Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp, a naturalised American of the twentieth

century, is the only other artist to create work at the mythic level and note

the logical conditions of its operation. Duchamp’s pervasive influence on

American and world cultures is considered elsewhere in this volume.

References

1 See 'Constitution of the United States', World Book Encyclopedia, Chicago, World Book Inc., pp. 996-1016. Back

Roger Peters Copyright © 2005

Back to Top

JAQUES

INQUEST

QUIETUS

ACQUITTAS

|