Roger Peters Copyright © 2005

JAQUES

INQUEST

QUIETUS

ACQUITTAS

Journal for the Advancement of the Quaternary Evolution in Shakespeare

Preamble

JAQUES is the cover-all title of a journal which incorporates essays about proto-quaternary thinkers (JAQUES), essays that investigate the historic misrepresentation of Shakespearean thought (INQUEST), and essays that examine social and political issues(QUIETUS). The essays will provide another level of evidence and argument for the presence of a consistent philosophy in Shakespeare's works, and for the claim that it is a philosophy unparalleled in the literatures of the world.

The intention in each essay is to lay down in general terms the relationship between Shakespeare's Sonnet philosophy and the topic to be critiqued. The idea is to show how the Sonnet philosophy resolves psychological problems consequent upon millennia of dependence on the inadequate biblical paradigm.

Preamble

George Lakoff is a cognitive scientist based at the University of California,

Berkeley, and Mark Johnson is a philosopher currently at the University of

Oregon. Together and separately they have produced a number of books

that argue, largely on the basis of empirical evidence, for the dependence

of the mind on bodily functions and dispositions. Their work challenges

what they call ‘2500 years of objectivist tradition’ in which the mind has

been viewed as transcendental and prior to the human body.

In books such as The Body in the Mind (1987) (1) by Mark Johnson, Women

Fire and Dangerous Things (1987) (2) by George Lakoff and co-authored books

such as Metaphors We Live By (1980) (3) and Philosophy in the Flesh (1999) (4), they

examine the way language is used and show that the majority of human

communication relies on metaphorical expressions that are so deeply

embodied in human experience that only by accepting the priority of the

body over the mind can the phenomenon be explained.

In Philosophy in the Flesh Lakoff and Johnson scrutinise the objectivist

tradition relentlessly to show that for 2500 years philosophical thought has

been based in wishful thinking rather than the natural logic of language.

They use their findings to critique traditional philosophy that has based its

speculative metaphysics on the illogical presumption that the mind is prior

to the body.

This essay considers the contribution of Lakoff and Johnson to the

post-Darwinian transformation in attitude to both language and the mind.

Darwin had demonstrated the priority of the body over the mind through

his scientific examination of the process of natural selection in evolution.

As a consequence of Darwin’s insights many philosophers have rejected

the tradition of justifying metaphysical claims and now accept the natural

logic of bodily priority. Lakoff and Johnson make special mention of

Maurice Merleau-Ponty and John Dewey who base their philosophies on

the understanding that ‘our bodily experience is the primal basis for everything

we can mean, think, know, and communicate’. (5)

But the essay also considers the difference between Lakoff and Johnson’s

claim that philosophy is a process of ‘inquiry’ best conducted by ‘empirically

responsible philosophers’ who propose philosophical theories, and

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s idea that philosophy continually reiterates the logical

conditions of life. If the logic of life is subject to ongoing empirical research,

as Lakoff and Johnson suggest, the implication is that until scientists finalise

their research no one can appreciate the logic of life.

Yet many people remain at ease with themselves and the world throughout

their lives, and no doubt many in the past have understood the natural

dynamic of life. The four thinkers who feature in these volumes (Darwin,

Mallarmé, Duchamp, and Shakespeare) despite working at the highest pitch

of intellectual achievement, were by all accounts philosophical about life.

The essay examines Lakoff and Johnson’s limited recognition of

Wittgenstein and questions why they decide not to examine his work when

they examine the contributions of other philosophers in the second part of

Philosophy in the Flesh. It then considers their determination to see philosophy

as a form of scientific inquiry into the mechanism of language without

subjecting the mythological language of male God biblical faiths to a similar

scrutiny.

Lakoff and Johnson’s reluctance to inquire into the culturally significant

language of myth and its sexual/erotic logic, despite the allusion to the

‘word made flesh’in the title of Philosophy in the Flesh, raises questions as to the

depth of their challenge to the objectivist tradition of the last 2500 years.

It is no surprise that Christian philosophers such as Augustine, Aquinas,

Descartes, and Kant never questioned the logic of the biblical mythology

because they were seeking to justify it using formal philosophical processes.

But ironically Lakoff and Johnson’s insistence that philosophy like science is

based in theories leaves them unable to do justice to the metaphor in

their title.

Four hundred years ago Shakespeare articulated the consistent mythic

logic of his Sonnets to correct the corrupt form of mythology in the biblical

texts. He shows that the logical elements for a consistent philosophy sought

by Lakoff and Johnson are available, though scrambled, in any mythology.

The essay will first consider the four books by Lakoff and Johnson

mentioned above, and then examine the relationship of their ideas to

Shakespeare’s philosophy.

Metaphors We Live By

In Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson present numerous examples of

metaphorical language to demonstrate that a large part of human communication

is based on metaphor. Unlike the traditional view of metaphor as an

accessory to language used only to evoke poetic insights or account for events

not otherwise understood, Lakoff and Johnson’s investigation shows that

everyday language is riddled with metaphoric references. The use of metaphorical

structuring in human communication is so pervasive they suggest

that ‘metaphor plays a very significant role in determining what is real for us’. (6)

So instead of being incidental, the occurrence of metaphor in language

is systematic. The instances of metaphorical structuring can be quite

complex with one form of metaphor ‘hiding’ another. For instance, in the

meta-language used to reflect on the use of language, their research identifies

three metaphors: ‘ideas are objects’, ‘linguistic expressions are containers’,

and ‘communication is sending’. (7) Lakoff and Johnson give a number of

examples of such metaphors in use, most of which are used unconsciously

in the give and take of daily discussion.

Metaphors We Live By discusses a range of ways in which metaphors enter

language as a consequence of bodily activity in the world. Language uses

many ‘orientational metaphors’ that correspond to bodily dispositions. The

words up, down, front, back, side, face, etc., are used universally to express

intention, emotion, decision and many other mental states. Lakoff and

Johnson describe the prevalence of ‘ontological metaphors’, ‘personification’,

and discuss the role of ‘metonymy’ in which a part stands in for the whole.

The interlacing of the various metaphorical expressions corresponds

systematically to aspects of human experience. The structure and coherence

of metaphors in language is a direct consequence of the structure and

coherence of everyday activities. While sentences expressing immediate

human requirements such as ‘pass the salt’ or ‘salt is good’ have no metaphorical

content, the distinctive capacity of humans to use language to

convey more complex ideas and desires is firmly grounded in the use of

metaphor. And just as factual sentences depend on bodily activities, the

language of metaphor is also based in bodily interaction.

Because the majority of human communication is based on metaphorical

language derived from bodily experience, Lakoff and Johnson say that

such metaphors are ‘grounded by virtue of systematic correlates within our

experience’ (authors’ italics). (8) They then use their empirical findings to critique

traditional philosophical ‘theories’. When they examine the notion of ‘truth’,

for instance, they find their understanding has elements in common with

‘correspondence theory’, ‘coherence theory’ and ‘pragmatic theory’ and

‘classical realism’. (9)

But for Lakoff and Johnson their ‘experientialist theory of truth’ takes

it as a ‘given’ that (summarising their points) the ‘world, cultures and people

are as they are’, that ‘people successfully interact with the world’, that ‘human

categorisation is constrained by reality’, that it ‘extends classical realism’s focus

on objects to people’, and that ‘human concepts correspond to interactional

properties and not inherent properties’. They then critique the ‘myth of

objectivism’, in which the ‘world is made up of objects’, and the ‘myth of

subjectivism’, which prioritises individual ‘feelings and intuitions’. (10) They

see their experientialist theory of truth reconciling Plato’s objectivist fear of

metaphor with Aristotle’s appreciation that metaphor makes it possible to

‘get hold of something fresh’. (11)

But Lakoff and Johnson do not offer a comprehensive philosophy of life

based on their empirical investigations. Instead they end their book with a

chapter on ‘understanding’. (12) They show how the ‘experientialist account

of understanding provides a richer perspective on…interpersonal communication,

self-understanding, ritual, aesthetic experience, and politics’. (13) As

this essay progresses and the comprehensive structure of Shakespeare’s Sonnet

philosophy is brought to bear on such musings, the consequence of Lakoff

and Johnson’s high expectation of scientific theories and their misunderstanding

of the status of myth will emerge.

Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things

In Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, Lakoff continues the work begun in

Metaphors We Live By but in greater detail and with greater attention to variations

across cultures. The title Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things derives from

the one of the four distinctive classifications of things in Dyirbal, an

Australian aboriginal language. The three items are in their second category

balan, which includes ‘human females, water, fire and fighting’. (14)

The principal focus of Lakoff ’s investigation, though, is still the contrast

between traditional ‘objectivism’ and ‘experientialism’. He first ‘defines’ the

‘issue’ that contrasts objectivism with experientialism. He asks if ‘meaningful

thought and reason concern merely the manipulation of abstract symbols

and their correspondence to an objective reality, independent of any embod-

iment’ or ‘do meaningful thought and reason essentially concern the nature

of the organism doing the thinking – including the nature of its body, its

interactions in its environment or its social character’. (15)

Lakoff begins by considering the importance of categorising to the

process of understanding and so for the possibility of understanding what

makes us human. Compared with classical categorisation based on ‘abstract

containers’ with things inside or outside, most human categorisation is done

automatically and unconsciously and includes every type of entity. He introduces

the work of Eleanor Rosch who questions the assumption that all

members of a category are the same or that they are unaffected by the peculiarities

of the beings doing the categorising.

In his second chapter Lakoff introduces the themes he will discuss. To

show the influence of human embodiment on categories he will consider

family resemblances, centrality, polysemy, generativity, membership gradience,

centrality gradience, conceptual embodiment, functional embodiment, basiclevel

categorisation, basic-level primacy, and metonymic reasoning. All the

themes are united under the umbrella of ‘cognitive models’, which structure

thought and are used in ‘forming categories and in reasoning’. (16)

It is not the intention in this essay to give any more than an indication

of Lakoff ’s exhaustive investigation of the embodiment in human language.

His book not only provides detailed evidence for such embodiment and

argues for experientialism against classic objectivism, it provides three

extended case studies of ‘recalcitrant’ ideas that classical techniques have been

unable to account for adequately.

Of interest to the findings presented in these four volumes is the

acknowledgment Lakoff gives Wittgenstein for his groundbreaking notion

of ‘family resemblances’ to characterise the properties found in conceptual

categories. But Lakoff avoids the logical overview Wittgenstein brings to

his understanding of the function of philosophy as a set of already existing

logical conditions that do not need to be proved or found but that are

frequently obscured from view. Lakoff ’s contrary belief that only empirical

investigation will reveal the logic of life and philosophic investigation is

unavailing will be critiqued as the essay continues.

The Body in the Mind

In The Body in the Mind Mark Johnson explores the role of the imagination

in the language dynamic. He wants to correct the ‘total absence of adequate

study of imagination in our most influential theories of meaning and rationality’.

(17) The problem can only be addressed by overturning the ‘widely

shared set of presuppositions that deny imagination a central role in the

constitution of rationality’17. The presumptions of the objectivist tradition,

with its ‘one correct God’s-Eye-View’, reduce the world to ‘objects’ that

are ‘independent of human understanding’. (18)

The empirical evidence from ‘studies in many different disciplines’

including cognitive science have demonstrated that ‘human understanding

is required for an account of meaning and reason’. (19) He lists categorisation,

framing of concepts, metaphor, polysemy, historical semantic change, non-

Western conceptual systems and growth of knowledge as phenomena that

challenge objectivist assumptions. As Hilary Putnam says, ‘any adequate

account of meaning and rationality must give central place to embodied and

imaginative structures of understanding by which we grasp the world’. (20)

Johnson illustrates the notion of ‘embodied imaginative understanding’

by considering two types of imaginative structure, image schemata and

metaphorical projections. He defines an image schema as a ‘recurring,

dynamic pattern of our perceptual interactions and motor programmes that

gives coherence and structure to our experience’. (21) The Body in the Mind

explores some of the more ‘important embodied imaginative structures of

human understandings that make up our network of meanings and give rise

to patterns of inference and reflection at all levels of abstraction’. (22)

Against the background of the objectivist tradition and continuing objectivist

expectations among many philosophers Johnson sees two ‘especially

controversial aspects in the view’23 he is developing about the centrality of

image schematic structures. The first is their ‘apparently nonpropositional,

analog nature’, and the second is their ‘figurative character, as structures of

embodied imagination’. (23) His intention is to build a ‘constructive theory of

imagination and understanding that emphasises our embodiment’. (24)

After providing a brief examination of objectivist theories of meaning

and rationality, with mentions of Descartes, Kant, Frege, Donaldson, and

others, Johnson concludes that image schemata have no place in objectivist

theories because they are ‘too bodily’ and because they are not ‘sufficiently

rule-governed’. (25) His procedure throughout the rest of the book is to

consider ‘embodied patterns of imagination’, the ‘role of bodily experience

in reason’, the ‘pervasiveness of image schemata’, and he then applies his

theories to ‘meaning, understanding, and imagination’. (26)

This is not the place to review Johnson’s detailed case for the embod-

iment of the imagination. It is sufficient to say that his arguments are in

accord with the attitude to the body/mind relationship articulated in these

volumes. But, as mentioned before, his insistence that philosophy is based

in theories restricts his ability to consider questions of the highest level of

imaginative engagement, the mythic. The absence is apparent in the last

couple of pages where he sketches a ‘non-objectivist account of truth’ and

then on the last page, through the agency of Hilary Putnam, he considers

the ‘coherence of our beliefs’. (27)

Putnam’s idea is that a ‘whole system of statements’ is rationally

acceptable through its ‘coherence and fit’, with ‘experiential beliefs’ and

‘theoretical beliefs…deeply interwoven with our psychology’. The resulting

objectivity is an ‘objectivity for us’ as against the ‘God’s-Eye-view’ of

religion. Johnson says he goes ‘beyond Putnam’s focus on beliefs’ to stress

the importance of the ‘public nature of image schematic and basic level

structures of understanding’ to provide a ‘shared human perspective’ that is

‘tied to reality through our embodied imaginative understanding’. (28)

This essay will show that only by understanding the function of the

deepest level of imaginative expression, the mythic, can the relation of the

psychology of beliefs and a sound philosophy be gained.

Philosophy in the Flesh

Philosophy in the Flesh begins by acknowledging those ‘empirically responsible

philosophers’ who draw on the ‘best available empirical psychology,

physiology, and neuroscience to shape their philosophical thinking’. (29) Then,

in the Introduction, Lakoff and Johnson list the ‘three major findings’ of

cognitive science: ‘the mind is inherently embodied’, ‘thought is mostly

unconscious’, and ‘abstract concepts are largely metaphorical’. (30) They are

confident the evidence from their research into the cognitive basis of language

brings to an end the a priori philosophical speculation of the last 2500 years.

For Lakoff and Johnson ‘our most basic philosophic beliefs are tied

inextricably to our view or reason’.30 As their findings are at odds with

‘central parts of Western philosophy’, they predict that philosophy will never

be the same again. They suggest their new understanding of the reasoning

process as inherently tied to bodily functions will provide a shock for traditional

philosophy. (31)

Then they list the differences between the new and the old views of

reason. Contrary to philosophical tradition cognitive science has shown that

reason is embodied, evolutionary, not universally transcendent, mostly

unconscious, largely metaphorical, and emotionally engaged. Looking at the

history of philosophy their findings overturn Cartesian dualism, Kantian

autonomy and universal morality, utilitarian economic rationalism, phenomenological

introspection, the poststructuralist decentred subject, Fregean

objective meaning, mind as computer theories, and Chomskyan genetic

syntax. (32)

For Lakoff and Johnson, past ‘philosophical questioning’ or ‘philosophical

reflection’ has not discovered the fundamental facts about the mind revealed

by their scientific investigation. Their programme in Philosophy in the Flesh

is to give an overview of ‘what philosophy can become’ by using the

‘methods of cognitive science and cognitive linguistics’. (33) Then in Part 2,

they analyse the basic concepts ‘that philosophy must address such as time,

events, causation, the mind, the self, and morality’ and begin the study of

‘philosophy itself ’ by examining the history of philosophy in Part 3.

Significantly, they do not address Wittgenstein’s ‘philosophy’ in the review.

Central to the task of understanding traditional subjects such as

metaphysics, morality, and the self by the new methods of cognitive science

is the appreciation that most cognition is carried on below the level of

consciousness. Here ‘cognitive’ refers not just to the conscious conceptual

or propositional structure of language but to ‘any kind of mental operation

that can be studied in precise terms’. (34)

Then, seemingly paradoxically, Lakoff and Johnson assert that even

though ‘we have no direct conscious awareness of what goes on in our

minds’ they are confident that ‘cognitive unconscious’ is accessible to

cognitive science through its theories. (35) They maintain that ‘unless we know

our cognitive unconscious fully and intimately’ (36) we cannot understand the

traditional subjects of philosophy.

Beginning with a chapter on the ‘embodied mind’, Lakoff and Johnson

review the findings of cognitive scientists about ‘primary metaphor and

subjective experience’, ‘the anatomy of complex metaphor’, ‘embodied

realism’, ‘realism and truth’, and ‘metaphor and truth’. In the final paragraph

of chapter 8, they concede that ‘the metaphoric character of philosophy is

not unique to philosophic thought. It is true of all abstract thought, especially

science’. (37) They acknowledge that even their cognitive scientific understanding

is available only through ‘conceptual metaphor’. They are confident

that the apparent difficulty, though, should not obscure their finding that

‘conceptual metaphor is one of the greatest of our intellectual gifts’. (37)

When Lakoff and Johnson turn to analyse basic philosophical ideas in

Part 2, they suggest their approach is ‘opposite’ to the common procedure

of applying a ‘purely philosophic methodology’. Instead of the ‘philosophy

of time’, for instance, they provide a ‘cognitive science of time’. (38) First they

acknowledge that ‘each idea has an underspecified nonmetaphorical

conceptual skeleton’ which is ‘fleshed out by conceptual metaphor’. But then

they say they will argue that each of the ideas is ‘not purely literal, but

fundamentally and inescapably metaphorical’. (38) Again their programme

seems somewhat paradoxical.

In Part 3, where Lakoff and Johnson examine the history of philosophy

from the perspective of cognitive science, they approach philosophy as a

‘form of conceptual activity’. (39) When ‘philosophers construct their theories

of being, knowledge, mind, and morality, they employ the very same

conceptual resources and the same basic conceptual system shared by

ordinary people in their culture’. Cognitive science ‘offers’ a conceptual

analysis of the ‘strange questions’ about such things as ‘being’, ‘truth’ and

‘good’. It provides a critical assessment of theories with ‘constructive philosophical

theorising’ about self understanding and how to act in the world. (40)

They end the Introduction by asserting that ‘all philosophic theories are

necessarily metaphoric in nature’. (41)

After reviewing the history of philosophy from the pre-Socratics to

Chomsky, Lakoff and Johnson conclude their book with an ‘empirically

responsible’ look at ‘person’, ‘evolution’, and ‘spirituality’. (42) Contrary to the

traditional western conception of the person, which is influenced by the

claim for God’s universality, they say that a person is embodied and has a

pluralistic morality. Turning to evolution, they recognise that it does not

entail ‘survival of the best competitor’ (43) because it could equally entail the

‘survival of the best nurtured’. They say ‘nothing of this sort is part of literal

evolutionary theory’. And the idea of the disembodied soul central to the

biblical tradition is a fiction only explicable through understanding how

humans perceive and think in their bodies through metaphor.

Lakoff and Johnson propose an ‘embodied spirituality’ because without

‘sex and art and music and dance and the taste of food’ spirituality is ‘bland’.

Their ‘philosophy in the flesh’ shows how our physical being with its ‘flesh,

blood, and sinew, hormone, cell, and synapse’ makes us ‘who we are’. (44)

From Lakoff and Johnson to Shakespeare

The weight of empirical evidence Lakoff and Johnson muster in support of

the priority of the body over the mind lends overwhelming scientific support

to the natural logic Shakespeare articulates in his Sonnets. Their investigation

of the significance of metaphor for cognitive processes shows that much of

human thinking is based in unconsciously stored bodily metaphors that

determine how the world is viewed. Their findings support the attitude

evident in Shakespeare’s drama, Duchamp’s art and Mallarmé’s poetry, which

are self-critical toward the imagery they use to convey meaning.

Yet despite the overwhelming support for natural logic from Lakoff and

Johnson’s empirical work, a number of times throughout their book they

equivocate over the relation between the literal and the metaphorical. While

sometimes recognising the presence of the literal, within a paragraph or so

they assert that all understanding is metaphorical. It is as if their intensive

research into metaphors continually forces out any consideration of the

significance of literal expression. They devote no space to explaining the

relation between the literal and metaphorical.

The essay will now consider the example of Darwin, Wittgenstein,

Duchamp, and then Shakespeare to show why philosophy involves the clear

understanding of the difference between the literal and the metaphorical.

Charles Darwin

Lakoff and Johnson’s demonstration that the body is prior to the mind

through their scientific analysis of cognitive processes is in complete

agreement with Darwin’s argument in The Descent of Man that the mind is

derived through evolutionary processes. In Darwin’s discussion of ‘mental

powers’ and ‘moral sense’ he shows that the mind exhibits no features not

explicable through evolutionary processes and that there is no support for

a belief in the separation of mind and body.

But while Lakoff and Johnson and Darwin arrive at the same conclusions

about the relation of the body and mind, their conceptions of the role

of philosophy are quite different. Whereas Lakoff and Johnson view

philosophy as just another area of understanding subject to scientific investigation,

Darwin uses his philosophic understanding to structure his investigations

and present his findings.

In The Origin of Species Darwin employs a philosophic approach advocated

by the philosopher William Whewell (1794-1866). To give the mass of

evidence he had accumulated in support of evolution a sound basis he

adhered strictly to the principle of vera causa. By first presenting evidence

for empirically observable phenomena he was able to make logical claims

about events not directly observable. Darwin organised Origin of Species so

that his work on artificial variation in domestic species became the basis for

his generalisations about natural variation over evolutionary time.

Darwin’s standing in the scientific community is a direct consequence

of his lifelong adherence to the principle of vera causa. His work has an

integrity and veracity unmatched by other writers whose findings involve

both direct observation and reasoned speculation. In terms of the difference

between the literal and the metaphorical established by Lakoff and Johnson,

Darwin first laid out his groundwork of literal observations before embarking

on his metaphorical suggestions for the prehistory of evolution. For him

philosophy was not a subject for empirical examination as it provided the

foundation on which everything else rested.

Darwin’s philosophy was not susceptible to theoretical revision. The

consistency of his life’s work rested on a secure philosophic foundation that

enabled him to explain successfully the evolution of ‘mental powers’ and

‘moral sense’. The opposite is the case for Lakoff and Johnson. Even though

the results of their empirical research are in accord with natural logic, their

equivocation about whether the literal is literal or unavoidably metaphorical

epitomises their confusion over the status and role of philosophy.

The consequence of Lakoff and Johnson’s subjection of philosophy to

empirical review is their conflation of the literal and metaphorical. They

were unwilling to appreciate that philosophy identifies the logical conditions

for understanding on which metaphorical cognitions are constructed.

The literal basis of language is the precondition for metaphorical development.

Darwin’s genius lies in never confusing his philosophic method

with his empirical investigations. The significance of Darwin’s appreciation

that philosophy provides the logical groundwork for any scientific investigation

(after all Lakoff and Johnson said that their scientific analysis was

couched in metaphor) will become apparent when Wittgenstein’s attitude

to philosophy is considered.

The other constant in Darwin’s philosophic approach is his awareness of

the sexual as the logical basis for the erotic logic of the human mind.

Darwin’s focus on the sexual in both The Origin of Species and in The Descent

of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex recognises that the sexual is the logically

prior condition for human persistence. In The Descent of Man Darwin first

considers the logic of human descent from mammalian forbears and then

spends two thirds of the volume considering secondary sexual characteristics.

From the literal status of the sexual evolves all the secondary sexual

characteristics including the erotic logic of the mind.

For Darwin, the sexual is the prototypical human activity in the logic

of evolution. The erotic dynamic of the mind follows from its prototypical

status. Yet in Lakoff and Johnson’s books on cognitive metaphor, the sexual

and the erotic barely rate a mention, and are not analysed systematically as

are traditional metaphysical concepts such as ‘being’, ‘cause’ and ‘time’ and

other theoretical concepts of academic philosophy. Lakoff and Johnson’s

unwillingness to investigate the pervasiveness of the sexual and sexual

metaphor across cultures shows an ignorance of Darwinian scientific

principles and blindness to his appreciation of the function of philosophy.

Ironically, in a book titled Philosophy in the Flesh Lakoff and Johnson do

not consider the sexual connotations of the word ‘flesh’. Nor do they

consider the role of metaphor in the highest form of metaphorical

expression, the mythological, where, for instance, the Son of God is called

the ‘Word made Flesh’. Even though they say they want to provide an

‘empirically responsible philosophy’ that critiques the ‘objectivist myth’ and

‘subjectivist myth’ of the last 2500 years, their use of the word myth to

characterise philosophical theories reveals an ignorance of the logical conditions

for mythic expression.

Ludwig Wittgenstein: the grounding of philosophy

The work of Ludwig Wittgenstein, who some consider the most profound

of the twentieth-century philosophers, offers a way to understand better the

relation between the literal and the metaphorical. While Lakoff and Johnson

acknowledge Wittgenstein’s contribution to removing ‘mistaken views about

conceptualisation and reasoning’ with his notion of ‘family resemblances’,

for them his work comes before the ‘age of cognitive science’.45 They do

not investigate his views on the function of philosophy or on the status of

‘philosophical theories’.

The absence of an extended discussion of Wittgenstein in Part 3 of

Philosophy in the Flesh, which considers a number of lesser philosophers, is

intriguing. The neglect is most likely because Wittgenstein’s understanding

of the function of philosophy is quite different from that expounded by

Lakoff and Johnson. Whereas they see philosophy as an ongoing procedure

similar to their investigations as cognitive scientists, and hence subject to the

critique of science, Wittgenstein understood philosophy as a way of seeing

the logical conditions for life as clearly as possible, and a way of critiquing

views that were at odds with the logical conditions for life.

So when Wittgenstein philosophised he accepted as a grounding those

things in life it makes no sense to question. Among these were the state of

‘nature’, ‘parents’, ‘family’, ‘forebears’, and the everyday objects and events

that form the basis of certainty. Wittgenstein is the first philosopher not to

use philosophical argument to justify a religious or otherwise metaphorical

understanding of the world. In Lakoff and Johnson’s terms, he first clarified

those things that are literal and then used them as a basis for evaluating the

logic of metaphorical speculations.

Wittgenstein progressed only gradually toward the clarity of his later

thought expressed in On Certainty but his attitude to the function of

philosophy remained constant throughout his life. In the Tractatus he hoped

to demonstrate the logic of the relation between the world and language

but failed because he was using the inappropriate atomism of Russell and

Frege. The world of discreet atoms and molecules did not have the correct

logical multiplicity to capture the complexity of language. His failure in the

Tractatus indirectly revealed the conceit in traditional metaphorical

theorising and led to his appreciation of the groundedness of understanding

in nature. He developed an approach based on life or nature, drawing on

natural metaphors to capture more exactly the logic of language.

In Wittgenstein’s second period of writing he determined that language

was subject like games to conventions or rules, but as with the infinite variety

of games there seemed to be no single set of criteria to apply to all language

games. Instead, language games were forms of life analogous to biological

relationships such as family resemblances. As language is logically a social

construct and not a private monologue, its rules could be examined to gauge

how words are used in everyday language. Wittgenstein argued that,

compared with the inconsistencies found in traditional metaphysical speculation,

everyday speech was logically sound. So an analysis of ordinary

language was more likely to reveal the structure and criteria for human

cognition and expression.

Contrary to Lakoff and Johnson, for Wittgenstein philosophy did not

entail proposing philosophical theories that were subject to scientific analysis.

Philosophy was the logical means to evaluate any form of expression

whether scientific or artistic for the consistency between its literal and

metaphorical statements. Even though Wittgenstein had difficulty accepting

all the implications of Darwinian evolution for the nature of the human

mind, he used the same approach as Darwin for maintaining a philosophic

poise throughout his life.

Lakoff and Johnson’s equivocation over the role of the literal has been

noted. As they are driven by their cognitive scientific discoveries in the realm

of metaphorical expression they could not accommodate the literal and so

cannot accommodate Wittgenstein’s challenge to 2500 years of philosophical

theorising to which they tied their project. Because they cannot appreciate

the logic of the literal then their assertions about the significance of

metaphor is awry, and their characterisation of ‘theories’ as ‘myths’ is symptomatic

of their unphilosophic approach to science. By claiming that

philosophy is based in theory they remain within the ambit of the academic

philosophy they critique in Part 3 of Philosophy in the Flesh.

Some of Wittgenstein’s last writings were on the philosophy of

psychology. He investigated rather simple optical illusions to better understand

the relation between ‘seeing’ literally and ‘seeing as’ metaphorically.

But despite his clarity about the function of philosophy Wittgenstein was

unable to develop a systematic expression of the relation between literal and

metaphorical languages. If Wittgenstein sensed a gap in his understanding

of language, Lakoff and Johnson seem not to be aware of the illogicality in

mistaking psychology for philosophy.

Marcel Duchamp: the sexual and the erotic

Philosophy in the Flesh, for reasons known to the authors, did not analyse the

metaphorical status of myth or examine the implications of its erotic logic.

Despite the metaphorical richness of their title they restricted themselves

to more prosaic metaphors and image schemas. In their final chapter Lakoff

and Johnson do consider the implications of the embodied mind for

‘persons’, ‘evolution’, and ‘spirituality’, where they discuss the idea of an

embodied God, but they end by advocating a panentheism in which the

divine is seen in all things (45). They are unable to identify the logical conditions

for mythologies much less the mythological basis of John’s Gospel,

which talks of the ‘word made flesh’.

Yet, if the history of metaphorical language is to be fairly scrutinised,

mythologies, as the most significant expression in the language, should surely

be subjected to the same investigative processes as bodily dispositions and

the history of ‘objectivist philosophy’. And if the sexual process is the logical

dynamic for the perpetuation of humankind then the erotic logic of

language should be the foremost in an analysis of the history of metaphor.

Lakoff and Johnson’s reluctance to make the sexual/erotic central in their

challenge to the objectivist tradition arises in part from the general ignorance

of the erotic logic of all mythologies. As long as mythologies were believed

to be literal stories where a male God creates the world and makes the male

then the female and then returns through a virgin to be reincarnated as his

own son, to die on a cross and be resurrected, then the eroticism central to

such stories was proscribed to the extent that no philosopher, even those as

secular or sceptical as Kant and Hume and Wittgenstein, has examined the

implications of eroticism in myth.

Only the work of Stephane Mallarmé and Marcel Duchamp begins to

grasp the deep illogicality of taking biblical mythology literarily. Mallarmé

was able to work past the illogicalities of his Christian upbringing to create

poetry of deep eroticism with an awareness that eroticism derives logically

from the sexual. His deeply symbolic poetry shows how to write with

consistency at a proto-mythic level.

Duchamp then took the process a step further. Learning from Mallarmé’s

achievement, his major work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

or the Large Glass, sets down the logical conditions for any mythic expression.

He purposely represents the female above the male to establish the

correct priority of female over male and shows how their unconsummated

relationship is basic to the erotic logic of artistic expression. He first accepts

the logic of the literal as a precondition and then gives it metaphorical expression.

In the Large Glass he takes that expression to its mythical limit without

losing the consistency of his original insight into the literal relations in life.

Lakoff and Johnson’s lack of awareness of Mallarmé and of Duchamp’s

achievement is not surprising, as Duchamp’s Large Glass has not received

the philosophic attention it warrants and only a critic like Octavio Paz has

shown an awareness of its critique of traditional mythologies. Without the

tools for mythic analysis critics end up speculating about Duchamp’s sexual

predilections, or turn hopefully to biblical or other mythologies.

Duchamp’s achievement is similar to Darwin’s in that both recognise the

need to reject the priority of the male-God prejudices of traditional beliefs

to arrive at consistent understanding. Their appreciation of the logic of art

and biology respectively inverts the literal belief in the biblical myths. Only

then can Darwin’s empirical research conform to his logical expectations.

And Duchamp first establishes the logical conditions for any artistic

expression before he makes readymade items of extraordinary simplicity but

with mythic impact.

Despite Lakoff and Johnson’s suggestion of a panentheism to replace the

illogicality of biblical priorities, they insist that only through empirical

evidence can the case against objectivism be won. Yet while Darwin’s case

was virtually undeniable through the preponderance of evidence alone, he

stands apart from all other evolutionary thinkers and the volumes of facts

disclosed in support of evolution by his logical exactness and rigour.

So there seems to be a co-relation between Lakoff and Johnson’s determination

to depend on the empirical and their unwillingness to provide

evidence if not argument for the role of the sexual/erotic in language. In a

personal comment Johnson said he was aware of the omission from

Philosophy in the Flesh and wanted to address the issues but Lakoff and he

‘agreed that there was not sufficient empirical evidence from their researches

to provide an adequate analysis’. But Darwin shows that no amount of facts

and figures can make up for an absence of logical insight in the challenge

to the illogicalities in traditional apologetics.

William Shakespeare

Shakespeare lived in the period when the methods of science were being

redefined by thinkers such as Francis Bacon. He was a contemporary of

Galileo and would have been aware of the astronomical theories of

Copernicus. There were also considerable advances in other sciences in the

Renaissance, particularly when compared with the relatively anti-scientific

attitude of the Mediaeval period.

Shakespeare’s interest in a philosophy grounded in natural observations

is evident in his regard for Aristotle, who challenged Plato’s otherworldly

idealism with a nature-based metaphysics and ethics. But Aristotle was still

conditioned by Platonic ideas about the place of man in nature and the roles

of men and women.

When the logic of Shakespeare’s Sonnet philosophy is considered it should

not surprise that his arguments are firmly based in observations of nature.

What could seem surprising to theory-based expectations of thinkers like

Lakoff and Johnson is that Shakespeare’s logic anticipates the discoveries of

Darwin, the language philosophy of Wittgenstein, the mythic logic of

Duchamp, and their own appreciation of the cognitive structure of language.

If it is possible to understand the world aright without waiting for the

results of scientific enquiry, then Shakespeare’s Sonnet logic seems to do just

that. It is both evidential and predictive in a way that Lakoff and Johnson’s

programme is not. A scientific approach using the theoretical tools of

cognitive science could not reveal the logic of mythic expression available

in the Sonnets.

When Shakespeare’s Sonnet logic is laid alongside Darwin’s logic, it seems

that 300 years previously he had accepted the logical priority of the body

over the mind. His argument that increase in nature from female and male

progenitors is prior to the possibility of truth and beauty not only correctly

places the body before the mind, it establishes the correct relationship

between aesthetics and ethics, something Lakoff and Johnson fail to derive

from their scientific analysis of language.

When the Sonnet logic is compared with the two periods of philosophy

of Wittgenstein, it provides a critique of the atomic model Wittgenstein

employed in the Tractatus by insisting that the human dynamic of male and

female in nature is the required model for the correct logical multiplicity

between language and the world. It anticipates Wittgenstein’s rejection of

the atomic model and his move toward a model based in nature and the

family dynamic.

The similarity between Shakespeare’s philosophy that lays down the

logical conditions for life and Wittgenstein’s attempt to do the same in his

second period counters Lakoff and Johnson’s claim that only science can

resolve philosophical problems. In fact the Sonnet philosophy encompasses

Wittgenstein’s two periods of philosophising. It is more consistently

systematic than the Tractatus hoped to be, and more true to life than

Philosophical Investigations was able to be.

The poetry of Stephane Mallarmé, with its densely metaphorical

symbolism, should be explicable by the scientific techniques of Lakoff and

Johnson. But if they are unprepared to investigate biblical expressions such

as ‘word made flesh’, then they are not in a position to appreciate Mallarmé’s

recognition that language as a product of the mind is logically erotic.

Mallarmé held Shakespeare in high regard and emulated his writing, giving

his own poetry a similar density of metaphorical allusion, though he lacked

Shakespeare’s mythic sensibility.

It is Marcel Duchamp who provides the logical connection between

Mallarmé and Shakespeare, even though Duchamp did not know of Shakespeare’s

comprehensive articulation of the mythic dynamic. Shakespeare

bridges the gap between Duchamp’s largely pictorial and barely annotated

appreciation of the mythic logic of art and Lakoff and Johnson’s demonstrations

of the corporeal logic of words in language. In his Sonnets he more

completely and precisely sets down the logical conditions for mythic

expression, and in his 38 plays and four longer poems he shows how to write

at a mythic level by using the sexual/erotic resources of language.

Shakespeare’s use of imagery, because it is based in the natural logic of

language that acknowledges the priority of the body over the mind,

conforms to Lakoff and Johnson’s critique of the objectivist tradition 400

years before their research laid bare the body schematic logic of language.

Shakespeare’s hierarchy of images conforms to Lakoff and Johnson’s determination

that categories of thought or objects are classified in language as

‘super ordinate, basic level, and subordinate’. (46) An analysis of Shakespeare’s

images by Caroline Spurgeon in Shakespeare’s Imagery (47) reveals a preference

for the prototypical as against the generic or the specific. He uses the generic

and specific in the speech of characters who are either pompous or foolish.

The organisation of the Sonnets is precise in its recognition of the priority

of the female over the male and the body over the mind or the sexual over

the erotic. The two sequences devoted to female and male and the 14

increase sonnets establish the physical basis for truth and beauty or the

dynamic of understanding.

But because the physical is archetypically sexual Shakespeare takes the

logical step avoided by Lakoff and Johnson to characterise the process of

thought and language as archetypically erotic. If Lakoff and Johnson had

carried out even a cursory examination of myths they would have recognised

the ubiquity of the erotic in all mythologies.

Conclusion

The erotic logic at the heart of all mythologies provides a reflexive acknowledgement

of the priority of the body over the mind. As works of literature

at the highest level, mythologies express the logical conditions for their effectiveness

as myth. Their erotic logic acknowledges the priority of the sexual

dynamic over the dynamic of the mind. The history of religious belief and

theology, though, has illogically concluded that the erotic basis of myth

points to a world beyond sexual contingency.

The logical mistake is at the crux of the problem Lakoff and Johnson

investigate empirically as cognitive scientists with their critique of the ‘objectivist’

tradition. But empirical evidence is not needed for an appreciation of

the logic of myth. Ironically the required logic is hinted at in their title

Philosophy in the Flesh.

Lakoff and Johnson’s engagement with the history of thought brings with

it an awareness not just of the body as the logical basis for language but of

the ‘flesh’ as the living vehicle for communication. But while their analysis

of traditional image schemas examines many aspects of human expression

they stop short of questioning the succinct expression of the word and flesh

in the mythic logic of the Bible.

By confining their challenge to the last 2500 years of the objectivist

tradition Lakoff and Johnson are unable to consider the origins of male

dominance and male God religions to see why philosophy became a matter

of justifying the status of the male God rather than articulating the logic of

life. If they expanded their perspective beyond the 4000 years since the male

usurpation of female priority and considered the evidence from the artifacts

of the last 30,000 years, they would see more clearly the reasons behind their

inability to appreciate the logic of life.

Lakoff and Johnson’s unwillingness to address the relationship between

literal language and embodied metaphor is symptomatic of the unwillingness

of the objectivist tradition to accept the primacy of nature and the priority

of the female over the male. The logic of life does not need the sanction of

scientific theories.

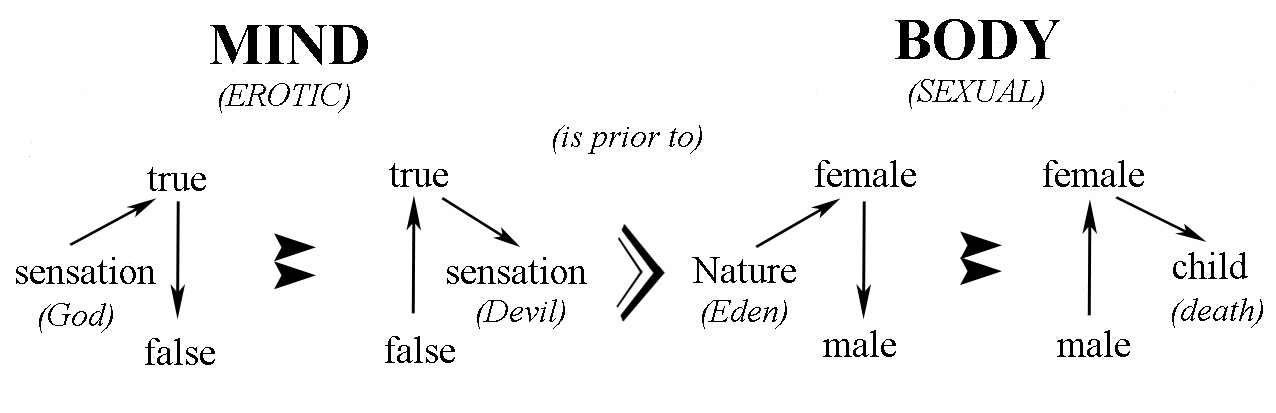

God Template

Lakoff and Johnson’s attack on the objectivist tradition using the tools

of cognitive science is an attempt to rectify the illogical consequences of the

God template derived in these volumes from Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Because

the objectivist tradition idealises the function of the mind, and seeks to

categorise ideas about the world into tidy sets, Lakoff and Johnson recognise

the need to invert the traditional views of the world.

But their challenge does not question the whole of the illogical God

template, and instead focuses on the relation of false and true and true and

false in the first part of the template. Because the dynamic of true and false

is the province of science, it becomes immediately clear why they equivocate

over the literal and the metaphorical, why they still talk of understanding

‘truth’, and why they are not drawn to critique ideas at the level

of the mythic.

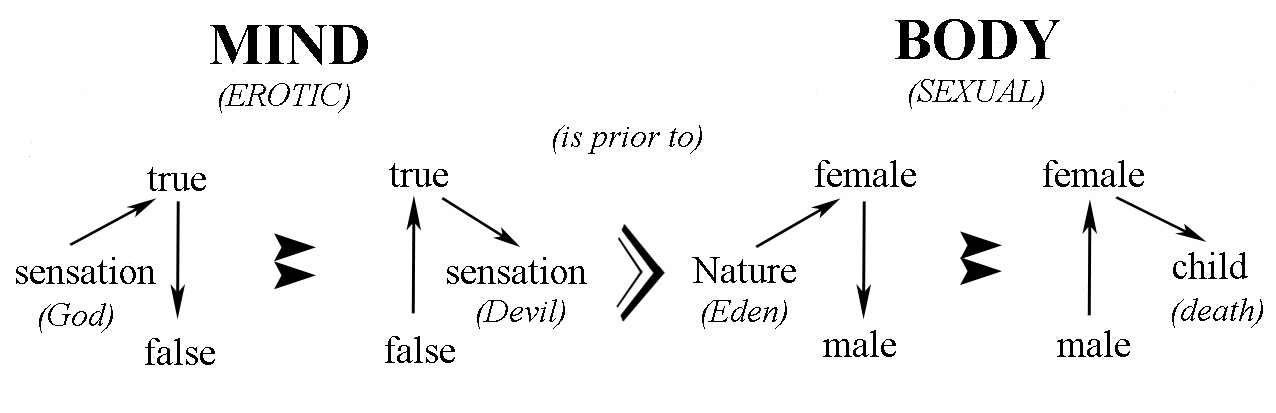

Shakespeare shows in his Sonnets that the only way to correct 4000 years

of male-based illogicality is to completely turn about the mythological

template behind traditional thought to re-establish the priority of nature

and the female so that the logic of language is not compromised. He is then

able in his plays to generate a mythic level of expression with consistency.

Nature template (Sonnet numbers)

The tendency for scientists to believe they can provide answers to the

unanswerable questions about human life in the universe, simply because

they can answer questions about observable phenomena, leads Lakoff and

Johnson to subject philosophical questions to their scientific programme. But

Darwin, at the highest level of empirical integrity, has shown that the role

of science is proscribed by the logic of life. And as Duchamp has shown,

the logic of myth can be expressed without an empirical programme, and

he also shows in the hilarious mechanisms of the Large Glass how the

pretences of science can be mocked in a work with mythic integrity.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets are exemplary in their combination of both

empirical observation of human behaviour and language and in their

expression of the logical conditions for any mythic possibility. They seem

to be the only text available that seamlessly combines an understanding of

the potentialities of the scientific and the possibilities of the mythic.

References

1 Mark Johnson, The Body in the Mind, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1987. Back

2 George Lakoff, Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, Chicago, Chicago of University Press, 1987. Back

3 George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1980. Back

4 George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Philosophy in the Flesh, New York, Basic Books, 1999. Back

5 Ibid., p. xi. Back

6 George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, p. 146. Back

7 Ibid., p. 10. Back

8 Ibid., p. 10. Back

9 Ibid., p. 180. Back

10 Ibid., pp. 186-8. Back

11 Ibid., pp. 189-90. Back

12 Ibid., p. 229. Back

13 Ibid., p. 230. Back

14 George Lakoff, Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, p. 92. Back

15 Ibid., pp. xv-xvi. Back

16 Ibid., p. 13. Back

17 Mark Johnson, The Body in the Mind, p. ix. Back

18 Ibid., p. x. Back

19 Ibid., p. xi. Back

20 Ibid., p. xiii. Back

21 Ibid., p. xiv. Back

22 Ibid., p. xvi. Back

23 Ibid., p. xx. Back

24 Ibid., p. xxi. Back

25 Ibid., p. xxxvi. Back

26 Ibid., p. xxxvii. Back

27 Ibid., p. 212. Back

28 Ibid., p. 213. Back

29 George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Philosophy in the Flesh, p. xi. Back

30 Ibid., p. 3. Back

31 Ibid., p. 4. Back

32 Ibid., p. 6. Back

33 Ibid., p. 8. Back

34 Ibid., p. 11. Back

35 Ibid., p. 12. Back

36 Ibid., p. 15. Back

37 Ibid., p. 129. Back

38 Ibid., p. 134. Back

39 Ibid., p. 338. Back

40 Ibid., p. 342. Back

41 Ibid., p. 345. Back

42 Ibid., p. 552. Back

43 Ibid., p. 561. Back

44 Ibid., p. 568. Back

45 Ibid., p. 567. Back

46 George Lakoff, Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, p.46. Back

47 Caroline Spurgeon, Shakespeare's Imagery: and what it tells us, Cambridge University Press, 1971. Back

Roger Peters Copyright © 2005

Back to Top

JAQUES

INQUEST

QUIETUS

ACQUITTAS

|