SONNETS 46-57

Sonnet 46

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war,

How to divide the conquest of thy sight,

Mine eye, my heart their picture’s sight would bar,

My heart, mine eye the freedom of that right,

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie,

(A closet never pierced with crystal eyes)

But the defendant doth that plea deny,

And says in him their fair appearance lies.

To side this title is impanelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart,

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eye’s moiety, and the dear heart’s part.

As thus, mine eye’s due is their outward part,

And my heart’s right, their inward love of heart.

Sonnets 46 and 47 examine the logic of the eyes, and their influence on the

mind and heart. Sonnet 46, particularly, shows why the logical relation of

‘thine eyes’ to ‘truth and beauty’, as defined in sonnet 14, is so basic to an

understanding of the whole set. Because most editors emend four instances

of the word ‘their’ in Q, to ‘thy’ (46.3,8,13,14), sonnet 46 provides an insight

into why the Sonnets are persistently misinterpreted.

Truth and beauty are not determined by the singular presence (thy) of

the youth or the Poet. Rather, from sonnet 14, both ‘thine eyes’ (14.9) of

‘thy sight’ (46.2) reveal what is in the mind and heart. The phrase ‘mine

eye’ (46.1,3) implies the two eyes of sight. The two eyes work together with

the mind to evaluate what they see in the eyes of others, (as in the ‘your

eye I eyed’ of sonnet 104). So, in each case, the plural ‘their’ refers to the

two eyes. So ‘their pictures sight’ (46.3) is the picture generated in the mind

by the eyes, and ‘their fair appearance’ (46.8) refers back to the role of the

‘crystal eyes’ at 46.6.

In sonnet 46, the visual image formed in ‘mine eye’ (46.1) is at ‘mortal

war’ with the unsighted feelings the Poet experiences in his ‘heart’.

Shakespeare’s ‘war’ is over the logic of perception and comprehension. Does

the eye or heart have priority in the formation of mental pictures? To ‘divide’

the ‘conquest of thy sight’ (46.2) the eyes (mine eye) would bar ‘their

pictures’ from the heart, and the heart would bar the eyes from the ‘freedom

of that right’ (46.4). The heart pleads that the youth lies within ‘him’ where

the evidence of the external world never ‘pierces’ (46.6). But the eyes of

the mind say the youth is ‘their fair appearance’ through the faculty of sight

(46.8).

The sides (46.9) in the ‘mortal war’ between ‘mine eye’ and ‘heart’ are

determined by the ‘verdict’ of a ‘quest of thoughts’ (46.10). Shakespeare

indicates his preference by calling the ‘thoughts’ tenants to the heart.

Consistent with the logic of beauty and truth articulated in the Mistress

sequence, thoughts (truth) and not feelings (beauty) decide the ‘title’. Before

the verdict is given the result is expressed in the ‘clear eye’s moiety’ (46.12)

and the ‘dear heart’s part’ (recalling the ‘dear religious love’ of sonnet 31).

In the couplet, the judgment is that ‘mine eye’s due is their outward part’

or that the eyes determine the image, which then can be used by the heart

to receive from the eyes ‘their inward love of heart’. So the eyes, mind, and

heart, are logically connected. Viewing eye to eye evokes a response in the

mind and heart. The ‘clear outward part’ and the ‘dear inward part’ are

distinct and yet united in the dynamic of truth and beauty.

Sonnet 47

Betwixt mine eye and heart a league is took,

And each doth good turns now unto the other,

When that mine eye is famished for a look,

Or heart in love with sighs himself doth smother;

With my love's picture then my eye doth feast,

And to the painted banquet bids my heart:

Another time mine eye is my heart's guest,

And in his thoughts of love doth share a part.

So either by thy picture or my love,

Thy self away, are present still with me,

For thou nor farther than my thoughts canst move,

And I am still with them, and they with thee.

Or if they sleep, thy picture in my sight

Awakes my heart, to heart's and eyes' delight.

Sonnet 47 continues the theme of sonnet 46. Sonnet 46 considered the

logical relationship of the eyes, mind and heart in terms of judgment and

love or truth and beauty. The four needless emendations of the ‘their’word

in sonnet 46 are made because the logic of the eyes presented in sonnet 14

as the basis for truth and beauty is not understood.

Sonnet 47 reiterates the logical distinction between ‘mine eye’ as the

portal to the mind for the dynamic of truth and the ‘heart’ as the locus of

internal sensations such as idealised beauty (47.1). There is a perpetual interaction

between the eyes and the heart where ‘each does good turns now

unto the other’ (47.2). Such good turns are needed when the eyes are

‘famished for a look’ or unable to see, or the heart is ‘in love with sighs’

(47.4) or smothers itself in self-regard.

So the eyes invite the heart to the ‘painted banquet’ (47.6) generated by

the eyes when they look on a painting of the youth, and in return the heart

hosts the eyes ‘in his (idealised) thoughts of love’ (47.8). Either by the

‘picture’ generated in the eyes or the ‘love’ in the heart, the Poet can

experience the youth even if he is away (47.10).

When the mind’s eye shares its picture with the heart and the heart shares

its thoughts of love generated in the mind, the Poet and the youth are as

one. The dynamic of truth and beauty, of separable thoughts and his singular

love, is logically available in the relation between the mind and heart. The

picture generated in the Poet’s eyes and the love then generated in his heart

substitutes for the absence or passing of youth.

In the couplet, it is only when the Poet’s mind and heart are asleep that

a picture of the youth appears in a dream for both heart and mind to ‘heart’s

and eyes’ delight’. The unity of the heart and mind’s eye while dreaming,

though, shows that the ‘league’ between ‘mine eye’ and ‘heart’ is a consequence

of giving the heart’s love priority over the mind’s eye.

The couplet recalls sonnet 43’s resolution of the difficulty the Poet had

in sonnets 27 and 28 in creating a picture of the youth in the darkness outside

without the aid of a painted portrait. In sonnet 47, the Poet revisits his

inability to bring an image of the youth to mind when looking into the

dark of night, and recounts his success when he sleeps and dreams.

Sonnet 48

How careful was I when I took my way,

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust,

That to my use it might unused stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust?

But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are,

Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief,

Thou best of dearest, and mine only care,

Art left the prey of every vulgar thief.

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art,

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part,

And even thence thou wilt be stolen I fear,

For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets are renowned for their poetic beauty and for their

expression of profound love. Sonnets 18 and 116, for instance, are rated

highly for their evocation of love and beauty. In the Sonnets, though, as in

Shakespeare’s plays and poems, love and beauty are logically inseparable from

the determination of truth. Love is based in the natural dynamic that

guarantees a logical relation between truth and beauty.

Throughout the Sonnets the emphasis shifts constantly from the lyrical

to the argumentative. Shakespeare’s poetry, even at its lyric height, never loses

its capacity for argument, and at its most argumentative it sustains an underlying

sense of beauty. He achieves both because he bases his sonnets in the

natural logic that informs the unity of the whole set of 154 sonnets, its two

sexually differentiated sequences, and the first 19 sonnets.

In sonnet 48, the logic of truth predominates over the logic of beauty.

In nearly every line there are words of praise and approbation. Truest, trust,

falsehood, worthy, best, thief, stolen, truth, thievish, and dear are some

examples. When the Poet questions how ‘careful’ he was when developing

his ‘way’ (48.1) or approach to life, he says he would have ‘thrust’ anything

he considered a ‘trifle’ under the ‘bars’ (48.2) of truth to prevent its false

use.

But the youth’s selfish idealism now ‘converts’ the Poet’s ‘jewels’ (48.5)

to ‘trifles’. If the youth was once the Poet’s ‘comfort’ he is now his ‘grief ’

(48.6). The youth has converted the ‘best’ of idealism to its ‘dearest’ or

costliest, making him ‘prey’ to the ‘every vulgar thief ’ (48.8) who perverts

natural logic.

The Poet does not restrict the youth’s freedom by having him ‘locked

up in any chest’ (48.9). The youth, as a persona of the Poet, is still within

the ‘gentle closure’ of the Poet’s ‘breast’ (48.11) from where he can ‘come

and part’ at his ‘pleasure’ (48.12).

In the couplet the Poet notes with irony that the youth, against the

dynamic of ‘truth’ articulated in the Sonnets, can be ‘stolen’by the false ideals

that are a ‘prize so dear’. Sonnet 48 concludes, as do many of the plays and

longer poems, that the logic of truth, when taken to a tautological extreme,

turns into its opposite. The youth’s ideal beauty hides its opposite, just as

the beautiful Rose hides its canker or thorns.

Sonnet 49

Against that time (if ever that time come)

When I shall see thee frown on my defects,

When as thy love hath cast his utmost sum,

Called to that audit by advised respects,

Against that time when thou shalt strangely pass,

And scarcely greet me with that sun thine eye,

When love converted from the thing it was

Shall reasons find of settled gravity.

Against that time I do ensconce me here

Within the knowledge of mine own desert,

And this my hand, against myself uprear,

To guard the lawful reasons on thy part,

To leave poor me, thou hast the strength of laws,

Since why to love, I can allege no cause.

In sonnet 49, the Poet considers the possibility of the youth being

‘converted’ (49.7) to a set of ‘laws’ (49.14) contrary to the Poet’s nature-based

logic. While there is no compulsion in natural logic for the youth to listen

to the Poet, the youth should be conscious of the logical consequences of

his decisions.

The Poet prepares ‘against that time’, if it comes, when the youth will

‘frown’ on his ‘defects’ (49.2). The Poet’s natural philosophy accepts the

dynamic of true and false as part of the logic of life. When the youth decides

to ‘cast his utmost’ or fateful ‘sum’ by remaining an adolescent idealist, he

will be called to ‘audit’ in ‘respect’ (49.4) of his decision. In sonnet 4, the

Poet encouraged the youth to understand the logic of increase in nature

or face her audit, and he is reminded again in sonnet 126.

The ‘utmost sum’ (49.3) is the numerological equivalent of the youth’s

decision (see the ‘sum of sums’ in sonnet 4). When the youth effectively

chooses the number 9 (126 = 1+2+6 = 9) and rejects the number 1 of

nature and the Mistress (28 = 2+8 = 10 = 1+0 = 1), he forgoes his potential

for unity and maturity (9+1 = 10 = 1+0 = 1). The youth could achieve

the unity of the Poet if he appreciated that the logic of love (sonnet 9) is

based on the logic of increase in nature.

The Poet prepares for when the youth will ‘pass’ him as a stranger,

‘scarcely’ greeting him because the idealistic ‘sun’ (as God) is in his ‘eye’

(49.6). The youth’s ‘love’ will have been ‘converted’ from its natural logic

for ‘reasons of settled gravity’ or traditional religious needs. The Poet

prepares to ‘ensconce me here’ (49.9) with the ‘knowledge of his own desert’

to defend the ‘lawful’ right of the youth to convert, despite the possible

consequences.

In the couplet, the Poet reflects that the youth’s departure from his loving

regard would be part of the natural law. Once the youth has made his

decision, then ‘love’ as the Poet knows it is no longer possible. Yet the Poet

knows that the youth’s conversion to selfish “niggarding’ (1.12) is still part

of natural logic for which he can ‘allege no cause’ because it is a potential

within nature. But it is a logical consequence that, if all were selfish like

the youth, humankind would not survive (sonnet 11).

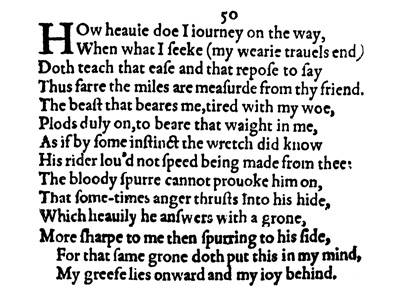

Sonnet 50

How heavy do I journey on the way,

When what I seek (my weary travel's end)

Doth teach that ease and that repose to say

Thus far the miles are measured from thy friend.

The beast that bears me, tired with my woe,

Plods duly on, to bear that weight in me,

As if by some instinct the wretch did know

His rider loved not speed being made from thee:

The bloody spur cannot provoke him on,

That some-times anger thrusts into his hide,

Which heavily he answers with a groan,

More sharp to me than spurring to his side,

For that same groan doth put this in my mind,

My grief lies onward and my joy behind.

Sonnet 51

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war,

How to divide the conquest of thy sight,

Mine eye, my heart their picture's sight would bar,

My heart, mine eye the freedom of that right,

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie,

(A closet never pierced with crystal eyes)

But the defendant doth that plea deny,

And says in him their fair appearance lies.

To side this title is impanelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart,

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eye's moiety, and the dear heart's part.

As thus, mine eye's due is their outward part,

And my heart's right, their inward love of heart.

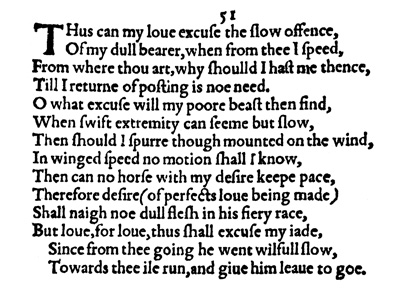

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence,

Of my dull bearer, when from thee I speed,

From where thou art, why should I haste me thence,

Till I return of posting is no need.

O what excuse will my poor beast then find,

When swift extremity can seem but slow,

Then should I spur though mounted on the wind,

In winged speed no motion shall I know,

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace,

Therefore desire (of perfects love being made)

Shall neigh no dull flesh in his fiery race,

But love, for love, thus shall excuse my jade,

Since from thee going he went wilful slow,

Towards thee I’ll run, and give him leave to go.

Comment on Sonnets 50 & 51

Sonnets 50, 51 and 52 are logically related with a ‘thus’ and a ‘so’. They

chart the journey of the Poet away from his youth into old age. In sonnets

50 and 51, the Poet parodies those who see age as a ‘burden’ and a cause of

‘grief ’. Then in sonnet 52 he reconciles the illogical idea of death being a

journey’s end with the potential of youth to achieve posterity through

increase.

Traditional commentators have tended to read sonnets 50 and 51 autobiographically

as an account of a period when Shakespeare was separated from

his ‘friend’. Hence they have been called ‘absence’ sonnets. Such a reading

though misses the parody Shakespeare makes of traditional conceits about

life and death and, more generally, ignores the evidence that sonnets 50 to

52 are an expression of natural logic. Significant also is Shakespeare’s

reflection on his recovery of a sound philosophy of life. The journey on a

‘jade’ away from or towards a youth is a metaphor for the relationship of his

old age to his own youth.

In sonnet 50 the Poet, with mock tiredness, describes the ‘heaviness’ of

the journey from youth to old age. If he seeks his ‘weary travel’s end’, it

‘teaches’ him the ‘ease and repose’ to ‘say’ (50.3) how far ‘the miles are

measured from thy friend’ (50.4). The logical potential of youth is the

measure against which traditional conceits about life and death are assessed.

The ‘beast that bears him’ (50.4) is the body that bears the Poet’s mind.

The body does not experience his mental ‘woe’ of bearing the ‘weight in

me’ of the idealised conceit of death that haunts his mind as the end of life’s

journey. The body’s ‘instinct’ (50.7) is logically predisposed to recognise the

potential of youth. It ‘knows’ (50.7) that the Poet or rider will return to its

natural logic. Physical abuse by the ‘bloody spur’, as a consequence of the

Poet’s mock ‘anger’ (50.10), cannot provoke the body because the effect

simply registers ‘more sharp’ (50.12) in the mind, which is doubly at fault.

In the couplet, the ‘same groan’ makes the Poet realise, or puts ‘this in

my mind’, that ‘grief ’ lies in viewing death as an end whereas his joy lies in

recognising the life potential of youth.

In sonnet 51, the Poet’s love can ‘excuse the slow offence’ (51.1) of the

body or ‘dull bearer’, because it is the body that shows up the mind’s error.

There is no need to ‘post’ (51.4) his progress to the youth, because the Poet’s

‘speed’ (51.2) is merely a mock of the traditional desire to be in another

world that would deny youth its potential to perpetuate human life.

The body or ‘beast’ can find no ‘excuse’ (51.5) because nothing can

explain the slowness when ‘swift extremity’ (51.6) is expected and ‘no

motion’ can be found in the ‘wind’ or in ‘winged speed’ (51.8). The Poet’s

mock expectation of a wonderful winged progress to death and beyond is

a fantasy, which the beast or body ‘knows’ intuitively.

The body or horse cannot ‘keep pace’ with such ‘desire’ (51.9), so desire

(because it is made of ‘perfects’ or idealised love) will not move the ‘dull

flesh’ (51.11) of the body. Only love based in the body or increase can

‘excuse’ or explain the reluctance of the ‘jade’ (51.12).

In the couplet, because the Poet’s body was so ‘willful slow’about leaving

youth, the Poet will no longer struggle with his ‘flesh’, but ‘run’ straight to

the potential of youth.

Sonnet 52

So am I as the rich whose blessed key,

Can bring him to his sweet up-locked treasure,

The which he will not every hour survey,

For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure.

Therefore are feasts so solemn and so rare,

Since seldom coming in the long year set,

Like stones of worth they thinly placed are,

Or captain Jewels in the carcanet.

So is the time that keeps you as my chest,

Or as the ward-robe which the robe doth hide,

To make some special instant special blest,

By new unfolding his imprisoned pride.

Blessed are you whose worthiness gives scope,

Being had to triumph, being lacked to hope.

The mock journey on an old ‘jade’ in sonnets 50 and 51 recounts the Poet’s

reconciliation of his flight from the logic of youth, where youth is the

‘portal’ to posterity. Sonnet 52 concludes the argument by celebrating the

Poet’s return to natural logic. In the octet, the Poet evokes the quality he

experiences when at one with his masculine and feminine personae. He has

reconciled the idealistic tendencies of his youth with the biological priority

of the female.

The Poet is now as ‘rich’ as those whose ‘blessed key’ (52.1), or penis,

can bring him to his ‘up-locked treasure’ (52.2) or woman’s sexual organs.

Once he is reconciled he need not ‘survey’ his treasure ‘every hour’ (52.3).

He is at ease, no longer needing to overindulge, so he can enjoy the ‘fine

point of seldom pleasure’. Because his understanding is balanced and

complete, his ‘blessed key’, or the appreciation of the significance of his

masculinity, is able to unlock the ‘sweet up-locked treasure’, or an appreciation

of the feminine.

The return to natural logic allows the Poet to ‘feast’ (52.5) even though

he seldom ‘comes’ (sexually) in the ‘long year’ (52.6). He is free in body and

mind to enjoy ‘feasts’ without ‘blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure’.

He appreciates the ‘treasure’ of his woman as if she were a ‘stone of worth’

or ‘Jewels in the carconet’ (52.8). Similarly, the youth is like a ‘chest’ or a

‘wardrobe’ with a hidden ‘robe’ that would make ‘some special instant special

blest’ (52.11) when his penis unfolds its ‘imprisoned pride’ (52.12). The pride

of the ideal, mocked in the heavy journey from youth, is liberated when

the youth appreciates the increase logic and accepts the priority of female

over male.

In the couplet, the Poet tells the youth he is potentially ‘blessed’, because

he can choose to use his ‘key’. His inherent ‘worthiness’ gives him the

necessary ‘scope’ either to have the realisation and so to ‘triumph’, or to ‘lack’

it and live forever in the realm of ‘hope’.

Sonnet 52 is set around the image of a key and a locked treasure. The

image provides a metaphor for the pen and paper the Poet uses to write

meaningful verse. It also allows an erotic symbolism that connects the poetic

expression of the Poet’s understanding to the physical world. Phrases such

as ‘blessed key’, ‘sweet up-locked treasure’, ‘blunting the fine point of seldom

pleasure’, ‘seldom coming’, ‘Jewels in the carcanet’ (the carcanet is a

necklace), ‘imprisoned pride’, and ‘scope’ have been chosen for their erotic

potential. The ‘rich’ phrases embody the richness of the Poet’s understanding

of life, and his capacity to express it in mythic verse.

Sonnet 53

What is your substance, whereof are you made,

That millions of strange shadows on you tend?

Since every one, hath every one, one shade,

And you but one, can every shadow lend:

Describe Adonis and the counterfeit,

Is poorly imitated after you,

On Helen's cheek all art of beauty set,

And you in Grecian tires are painted new:

Speak of the spring, and foison of the year,

The one doth shadow of your beauty show,

The other as your bounty doth appear,

And you in every blessed shape we know.

In all external grace you have some part,

But you like none, none you for constant heart.

Throughout the 126 sonnets to the youth, the Poet identifies the characteristics

that typify youth and indicates the characteristics that will enable

the youth to become a mature person or poet. The idealism of youth drives

the youth’s hopes and aspirations. Unchecked idealism, though, creates

fantasy or shadow worlds. In the Sonnets, the Poet seeks to correct the

negative consequences of idealism and condition it with a mythic logic based

in the natural world. He advocates maturity founded on the inherent logic

of life.

In sonnet 53, the Poet questions the status of the youth’s ‘substance’

(53.1) or his basic nature. If ‘millions of strange shadows’ (53.2) contribute

to the youth’s appearance then what constitutes his substance or his relation

to others? If ‘every one’ has an identifiable personality, or ‘one shade’ (53.3),

how can the youth’s identity be borrowed from every ‘shadow’ (53.4).

When the naturalness of youth is compared with Adonis, the Greek

demi-god, Adonis is a ‘counterfeit’ (53.5). And the youth’s natural qualities

make him appear ‘new’ (53.8) when they are compared with the beauty set

on ‘Helen’s cheek’.

Rather the youth should be compared to the ‘beauty’ of ‘spring’ and the

‘foison’ or bounty of Autumn (53.9). Spring shows him the ‘shadow of his

beauty’ (53.10) or his potential for increase, and the ‘other’ is his bounty if

he exercises his right to increase. Because he is part of the natural world he

is in ‘every blessed shape we know’ (53.12).

In the couplet, the youth’s ‘part’ in the ‘external grace’ of nature is

guaranteed by his being part of the genealogical tree of ‘millions of strange

shadows’. And being the ‘newest’ in line, he is like no other. ‘None’ is like

him for having a ‘constant heart’, or appreciating the basis of love in natural

logic. Because commentators ignore the logic of the increase sonnets they

quibble over the apparent hyperbole in ‘millions of strange shadows’.

Sonnet 54

Oh how much more doth beauty beauteous seem,

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give,

The Rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem

For that sweet odour, which doth in it live:

The Canker blooms have full as deep a dye,

As the perfumed tincture of the Roses,

Hang on such thorns, and play as wantonly,

When summer's breath their masked buds discloses:

But for their virtue only is their show,

They live unwoo'd, and unrespected fade,

Die to themselves. Sweet Roses do not so,

Of their sweet deaths, are sweetest odours made:

And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth,

When that shall vade, by verse distils your truth.

Sonnet 54 mentions both beauty and truth. In the Sonnet logic, ‘beauty’ is

associated with the sensation of beauty typical of the Rose. And beauty as

sensation is complemented by the logic of ‘truth’ as saying, associated

throughout the Sonnets with the Muse. The Muse, as the inspiration for

saying, is associated with ‘argument’, ‘thought’, ‘language’, ‘words’, and so

the capacity of verse to express content. The susceptibility of beauty or the

Rose to canker or disease relates beauty to the dynamic of truth.

In sonnet 54, Shakespeare uses the image of the Rose three times to

convey the logic of truth and beauty. ‘Beauty’ (54.1) cannot be self-sufficient.

Like the Rose it is always susceptible to canker. Only beauty in its

logical relation to the dynamic of truth can be truly ‘beauteous’. The Rose

‘looks fair’ (54.3) or beautiful but it is the combination of two traits, visual

beauty and a ‘sweet odour’ (54.4), that makes it ‘fairer’, or able to engender

the dynamic of truth. The Rose and odour together create the required

discrimination for the logic of beauty and truth combined.

By contrast, ‘Canker blooms’ (54.5) or hedge roses, which look as

beautiful, lack the additional quality or ‘perfume’ that the Poet identifies with

the possibility of truth. With their singular beauty as their ‘only show’(54.9),

these roses ‘die to themselves’. ‘Sweet Roses’ by contrast continue to give

off ‘the sweetest odours’ (54.12) when they die. Beauty, when it remains

alone, is a transitory phenomenon that fades. Only the added dynamic of

truth ensures that beauty does not remain ‘unwoo’d’ (54.10).

In sonnet 54, the Poet combines the argument of sonnet 8, which

advised the youth to make music with more than one string, with the logic

of beauty and truth, to demonstrate their isomorphism. The veracity of the

Poet’s verse is guaranteed by the natural logic of the relation between body

and mind.

In the couplet, the Poet draws the parallel between the logic of beauty

and truth and the youth’s potential for increase. When the beauty of the

youth fades, the logic of beauty and truth conveyed by the Poet’s verse

‘distils’ the ‘truth’ of the youth’s situation. Has he been a canker or a sweet

bloom? Because the Poet’s verse expresses truth and beauty consistent with

the increase dynamic in nature, then ‘by’ his verse the youth sees truth

‘distilled’.

Some editors change the ‘by’ of the last line to ‘my’, thinking the youth

is being immortalised in the Poet’s verse. Rather the youth is being evaluated

‘by’ the standard of the Poet’s verse established by the whole set of 154

sonnets.

Sonnet 55

Not marble, nor the guilded monument,

Of Princes shall out-live this powerful rhyme,

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone, besmeared with sluttish time.

When wasteful war shall Statues over-turn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword, nor wars quick fire shall burn:

The living record of your memory.

'Gainst death, and all oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth, your praise shall still find room,

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

So till the judgment that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lovers' eies.

Traditionally sonnet 55 and other sonnets such as 18, 116, and 129, are interpreted

as offering immortality through poetry. The claim arises, though,

from the application of the inappropriate Judeo/Christian paradigm to

Shakespeare’s natural logic. Indicative of the prejudice brought to the sonnet

is the capitalisation of the word ‘judgment’ (55.13), which in Q has a lower

case ‘j’. The word judgment is not capitalised because it refers back to the

logical ‘judgment’ (14.1) the youth has to make in the last of the increase

sonnets. But many editors presume ‘judgment’ refers to the Christian

Judgment Day, so they assign it a capital ‘J’.

Sonnet 55 opens by claiming the Poet’s ‘powerful rhyme’ (55.2) will

outlive ‘marble’ and the ‘guilded monument, of Princes’. The youth will

‘shine more bright in these contents’ (55.3) or ‘powerful rhyme’ because,

unlike ‘unswept stone’, the youth can avoid physical decay through time

through the ‘contents’ of Shakespeare’s Sonnets (55.4). The ‘contents’ of the

Sonnets include the logical realisation that only by increase will the youth

persist, and only through increase will truth and beauty escape its ‘doom

and date’ (14.14).

The ‘contents’ of the Poet’s ‘rhyme’establish the logical condition under

which the ‘living record’ of the youth’s ‘memory’ (55.8) will not be erased

by the destruction of ‘statues’ and ‘masonry’ (55.6) and the depredation of

‘sword’ and ‘fire’ (55.7). The ‘living record’ is the genealogical persistence

through time of humankind. The ‘memory’ is the youth’s genealogical

relation to other human beings.

According to the ‘living record’ or ‘contents’ of the Poet’s verse, the youth

will ‘pace forth’ against ‘death, and all oblivious enmity’ (55.9). So, if the

youth is perpetuated in the eyes of ‘posterity’ (55.10), then his qualities will

be praised. This is the ‘posterity’ mentioned in sonnet 3. The only condition

that will terminate such a possibility would be the failure of humankind to

increase. If there is no increase then the human race will meet its ‘ending

doom’ (55.12) despite its faith in a male God.

In the couplet, the ‘judgment’ the youth must make is whether he will

‘rise’ and ‘live’ through posterity and so dwell in ‘lovers’ eies’. Sonnet 9

identifies the regard for human posterity as the logical source for the many

forms of human love. Sonnet 14 identifies the ‘eyes’ as the source of truth

and beauty. And the eye is also a symbol for the sexual organs. So sonnet

55 brings together the concerns of sonnet 54 where the ‘Rose’ with its

anagram Eros is similarly a symbol for both mind and body. In the Sonnets

the relation of the body and mind is rendered harmonious.

Sonnet 56

Sweet love renew thy force, be it not said

Thy edge should blunter be than appetite,

Which but today by feeding is allayed,

Tomorrow sharpened in his former might.

So love be thou, although today thou fill

Thy hungry eies, even till they wink with fullness,

Tomorrow see again, and do not kill

The spirit of Love, with a perpetual dullness:

Let this sad Int'rim like the Ocean be

Which parts the shore, where two contracted new,

Come daily to the banks, that when they see:

Return of love, more blest may be the view.

As call it Winter, which being full of care,

Makes Summers welcome, thrice more wish'd, more rare.

The Sonnet philosophy provides the logical structure within which the

meaning of each sonnet is located. Because Shakespeare’s understanding

recognises nature as prior to all else, he achieves a balance and perspective

unavailable to traditional religions based on the illogical priority of a male

God over nature. The short-term social/political and psychological

ambitions of such religions make them prone to division and intolerance,

as occurred with a vengeance in Shakespeare’s day.

In sonnet 52, the Poet advised the youth not to ‘blunt the point of

seldom pleasure’. Now, after sonnet 55 has focused the youth’s attention on

the ‘living record’ or ‘contents’ of the Poet’s verse, sonnet 56 repeats the

advice. It doubles the appeal to the youth by wanting him to be contented

(both meanings are evident in the first sonnet of the set) by encouraging

him not to blunt his ‘appetite’ (56.2).

Rather than let the youth’s sexual ‘edge’ be ‘blunter’ than his ‘appetite’,

the Poet tells his ‘sweet love’ to ‘renew thy force’ (56.1). If ‘today’ the youth’s

appetite is allayed by ‘feeding’, then ‘tomorrow’he should allow it to sharpen

‘in his former might’ (56.4). The Poet’s argument throughout has been a

logical one for the priority of increase over truth and beauty. But the youth

should not interpret it as a justification of sexual license. As in sonnet 41,

the abuse of a ‘woman who woes’ is as illogical as selfish abstinence.

The Poet then repeats his advice, though this time with a keener sense

of sexual punning. The logical relation between the eyes of vision and the

sexual eyes is apparent in the ‘hungry eyes’ (56.6), which ‘wink with fullness’

but which should ‘tomorrow see again’ rather than ‘kill the spirit of Love,

with a perpetual dullness’ (56.9).

The natural logic of the Sonnets is evoked here when the Poet advises

the youth to let the ‘Interim’ between ‘loving’ be ‘like the Ocean’ (56.9).

The priority of Nature as the sovereign mistress, and the Mistress with her

lunar number 28, makes the symbolic identification of the Ocean as female

the appropriate metaphor for the Poet’s intent. The youth, when ‘contracted

new’(56.10), should approach the relationship as if visiting a ‘shore’ to await

the ‘return of love’ (56.12).

In the couplet, the ‘Interim’ for the youth is called a caring ‘Winter’.

Out of its seeming sparseness are generated many ‘Summers’, three times

more than ‘wished’ for and ‘more rare’. Shakespeare’s art is ‘rare’ because he

bases his understanding in natural logic rather than in pious hope.

Sonnet 57

Being your slave what should I do but tend,

Upon the hours, and times of your desire?

I have no precious time at all to spend;

Nor services to do till you require.

Nor dare I chide the world without end hour,

Whilst I (my sovereign) watch the clock for you,

Nor think the bitterness of absence sour,

When you have bid your servant once adieu.

Nor dare I question with my jealous thought,

Where you may be, or your affairs suppose,

But like a sad slave stay and think of nought

Save where you are, how happy you make those.

So true a fool is love, that in your Will,

(Though you do any thing) he thinks no ill.

Sonnets 57 and 58 are linked by the image of the Poet as a ‘slave’ who was

once at the mercy of ‘God’ (58.1). After the appeal in sonnet 56 to the

‘Ocean’ as a symbol of both Nature the sovereign mistress and of the

Mistress, sonnet 58 introduces the word God into the Sonnets for the first

time. Sonnets 57 and 58 are exceptional for the unrelenting focus with

which Shakespeare examines the strengths and the failures of religious ideals,

here clearly associated with the image of the male God. ‘God’ represents the

enslaving ideal, which has a strong hold on the mind of the Master Mistress.

Shakespeare examines the logical conditions for ‘beauty’ and ‘truth’ in

the Mistress sequence. Beauty is any form of sensation of which the sensation

of the ideal in the mind is the most intense. Truth as ‘saying’ is the capacity

to discriminate between the ideas of true and false or good and evil inherent

in any sensation. So when the Poet attempts to educate the youth in the

logic of truth and beauty in the Master Mistress sequence, one of his aims

is to show the good and evil inherent in the singular idea of God.

When the Poet addresses the idealism of the youth in the first 126

sonnets, he also re-evaluates his own youthful idealism. Because of the

bloody conflict in Shakespeare’s day between rival Christian sects for the

ownership of ‘God’, the first line of sonnet 58, ‘That God forbid, that made

me first your slave,’ identifies the particular form of idealism that may have

led Shakespeare to unravel the contradictions in male-based religions.

Sonnet 57 begins the examination by considering the youth’s idealism

in general terms. The Poet asks rhetorically ‘what should I do’ (57.1) if he

is a ‘slave’ to the ‘hours, and times’ of the youth’s ‘desires’. As long as the

Poet is subject to the youth’s illogical requirements, he can perform no other

‘services’ (57.4).

Shakespeare identifies the slavery of idealism with the consciousness of

the ‘clock’ of time. The natural world is ‘without end hour’ (57.5) or free

of temporal constraints. But the youth attempts to become ‘sovereign’ (57.6)

by replacing the persistence of life in sovereign mistress Nature with a

morbid sense of ending time. The Poet, though, shows no ‘bitterness’ at the

youth’s wilful ‘absence’. He cannot ‘question with my jealous thought’ (57.9)

the youth’s whereabouts or his ‘affairs’. He is forced to remain a ‘sad slave’

(57.11) thinking on the happiness the youth brings to others.

The couplet observes that as 'love' is a canny ‘fool' (like the fools in Shakespeare's plays) it can accommodate such a wilful

youth, and ‘think no ill’ of him when he does ‘anything’ he ‘Will’. The play

on Shakespeare’s name reinforces the double reference of the sonnet to an

idealistic youth and Shakespeare’s youthful experiences.

Back to Top

Roger Peters Copyright © 2005

Introduction

1-9

10-21

22-33

34-45

46-57

58-69

70-81

82-93

94-105

106-117

118-129

130-141

142-153

154

Emendations

|