SONNETS 58-69

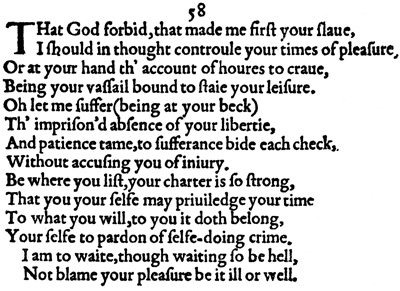

Sonnet 58

That God forbid, that made me first your slave,

I should in thought control your times of pleasure,

Or at your hand th’account of hours to crave,

Being your vassal bound to stay your leisure.

Oh let me suffer (being at your beck)

Th’imprisoned absence of your liberty,

And patience tame, to sufferance bide each check,

Without accusing you of injury.

Be where you list, your charter is so strong,

That you your self may privilege your time

To what you will, to you it doth belong,

Your self to pardon of self-doing crime.

I am to wait, though waiting so be hell,

Not blame your pleasure be it ill or well.

Sonnets 57 and 58 are linked by the common imagery of enslavement

to the ideal. While the Mistress sequence presents the logical conditions for

beauty and truth, the youth sonnets focus particularly on the traditional

confusions over the logic of the ideal. The introduction of the male ‘God’

of religion in sonnet 58 intensifies the arguments of the previous sonnets.

As noted, sonnet 58 is the first in the set to use the word God. The only

other sonnet in the youth sequence to use the word is sonnet 110. In both

cases in the 1609 original, the word God has a capital ‘G’. Most modern

editions omit the capitals. The only other use of ‘God’ is in sonnet 154,

where ‘the little Love-God’ is the Roman ‘Cupid’ named in sonnet 153.

The poet Ted Hughes speculates in Shakespeare and the Goddess of

Complete Being on the profound effect the religious excesses of the

Reformation may have had on Shakespeare. His family and others suffered

persecution in the name of God as two sects fought over the absolute right

to the ideal. So his use of the word God in sonnet 58 could reflect both

logical and personal issues.

Sonnet 58 identifies ‘God’ as the one who first made the Poet a ‘slave’

to his youth. The paradox is that if the Poet ‘in thought’ (58.2) wants to

‘control’ the youth’s ‘pleasure’, or make an ‘account’ of the hours the youth

‘craves’, how can a slave ‘stay your leisure’ (58.4). Being a slave to the mindbased

sensation of the singular ideal (God), precludes an argument against

unthinking sensuous indulgence.

The Poet facetiously offers to suffer ‘imprisoned absence’ (58.5) and to

exercise ‘patience’ at the ‘checks’ caused by the youth’s ‘liberty’, without

accusing him of ‘injury’ (58.8). If God, as the archetypal male adolescent,

makes the Poet a slave, and he suffers the constraint, then he cannot exercise

his ‘thoughts’ or the dynamic of truth to accuse the youth of injury.

Sonnet 57 stated that only a ‘fool in love’ would ‘think no ill’ of such

behaviour. So in sonnet 58, the Poet asserts that the God-based ‘charter’

(58.9) the youth uses to sanction his willfulness, encounters the contradiction

as to how ‘your self to pardon of self-doing crime’ (58.12).

The couplet is uncompromising. If the youth expects the Poet ‘not to

blame (his) pleasure be it ill or well’, then the Poet may as well be waiting in

‘hell’. Because the ideal as the absolute good is unmitigated sensation, it

becomes indistinguishable from its evil consequence. Sonnet 58 details the

wrong that comes from thinking ‘no ill’ (57.14). Together sonnets 57 and 58

assert that the idealised male God, divorced from the capacity to determine

right and wrong, readily becomes its logical counterpart, the evil of ‘hell’.

Sonnet 59

If there be nothing new, but that which is,

Hath been before, how are our brains beguiled,

Which labouring for invention bear amiss

The second burthen of a former child?

Oh that record could with a back-ward look,

Even of five hundreth courses of the Sun,

Show me your image in some antique book,

Since mind at first in character was done.

That I might see what the old world could say,

To this composed wonder of your frame,

Whether we are mended, or where better they,

Or whether revolution be the same.

Oh sure I am the wits of former days,

To subjects worse have given admiring praise.

When the Sonnets are compared with those of other sonneteers, only

Shakespeare’s are based in nature and have an increase argument logically

structured into the sequence that allows for a consistent development of

ideas. No poet, playwright, or philosopher before or since has incorporated

such a rigorous argument for sexual increase into a poetic masterpiece.

So when Shakespeare looked about, he must have been acutely aware

of the difference between his logically structured verse and the psychological

concerns of others. His skill and self-effacement had enabled him to see

more deeply into the logic of life and the artistic process. So he must have

been bemused to see others ‘labouring for invention’ (59.3) when the success

of his works was based on a principle they ignored or even disparaged.

Sonnet 59 records Shakespeare’s deep sense of irony about other minds

who overlook the obvious. The Poet says his understanding is ‘nothing new,

but that which is’ (59.1). How, he asks, are ‘our brains beguiled’ (59.2) into

‘labouring’ (59.3) for the ‘invention’ of ideas contrary to the logic of the

increase, and the dynamic of truth and beauty. (The ‘labouring’ metaphor

signals the presence of the increase argument.) How can human understanding

‘bear amiss’, or misrepresent as ideal, the anthropomorphic potentialities

or ‘burdens’ (59.4) that pass from child to child according to the logic

of increase.

The Poet wishes there was a ‘record’ (59.5) in an ‘antique book’ for a

‘back-ward look’ over the last 500 years since the time that ‘mind’ (59.8)

was able to ‘character’ an image of the youth in writing. The Poet could

then see if the ‘old world could say’ (59.9), in comparing the ‘composed

wonder’ of the youth’s ‘frame’, whether ‘we are mended’, or where they were

‘better’, or whether, as he suspects, mind and frame have remained the ‘same’

(59.12) for each revolution of the sun.

In the couplet the Poet concludes, somewhat facetiously, that the ‘wits

of former days’must have had ‘subjects worse’ to praise than the idealising

youth, who is ignorant of the increase argument. If through ‘five hundreth

courses of the Sun’ human beings have persisted through childbirth, yet have

frequently denied its logical significance, then anything is possible now. How

otherwise to explain vain attempts to invent subjects better than those that

motivated Shakespeare’s poems and plays.

Sonnet 60

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end,

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned,

Crooked eclipses 'gainst his glory fight,

And time that gave, doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth,

And delves the parallels in beauty's brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow.

And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

If the logic of the Sonnets represents Shakespeare’s understanding, then its

patterns of thought should be evident in individual sonnets. As the whole

set is characterised by Nature, the sovereign mistress, it is nature who determines

that the youth should be brought into the correct relationship with

the Mistress. The Poet, as the one who has come to understand the logic

of his youth, gives it expression. If the youth does not respond, then time,

nature’s agent, will enact the consequences.

Sonnet 60, which mentions minutes, is devoted to the theme of time.

It recalls sonnet 12, which mentions hours. The Poet compares the progress

of ‘waves’ toward the shore to the way minutes ‘hasten to their end’ (60.2).

The breaking waves are ever ‘changing place with that which goes before’

(60.3) evoking the sense of time moving forward but standing still. If sonnet

59 argued there was nothing new in 500 years of increase, in sonnet 60 the

illusion is of ‘sequent toil’ in which ‘all forwards do contend’ (60.4).

The continuity of nature and the persistence of life through increase

provide the logic for understanding time. Hence time, which the idealistic

youth/God sees as eternal, is visualised as an ever-recurring phenomenon at

the edge of the great sea that is the Mistress. The 28 sonnets to the Mistress

identify her with the lunar cycle, and so the tidal effect of the beach and sea.

As with the ‘labouring’ in sonnet 59, the Poet reflects that ‘nativity’ (60.5)

or increase was once considered central to existence (‘once in the main of

light’). The ‘crowning’ moment of human ‘maturity’ (60.6) in increase has

been confounded by ‘crooked eclipses’ or beliefs and superstitions that ‘fight’

(60.7) against the ‘glory’ of the youth’s natural ‘gift’ (60.8). ‘Time’ has had

its role shifted from fostering increase to explaining away death and ‘doth

now his gift confound’.

‘Time’ is a concern only for those who wish to ‘transfix’ (60.9) the significance

of increase, or nail down the potential ‘flourish set on youth’, and so

furrow his ‘brow’ (60.10). They ‘feed’ on the ‘rarities of nature’s truth’

(60.11) or the moment of death, but offer ‘nothing’ except objects for time’s

‘scythe to mow’.

In the couplet, the Poet expresses his ‘hope’. His verse, which in its philosophic

consistency offers an understanding true to nature, praises the youth’s

inherent ‘worth’ as part of the lineage of human beings. The Poet’s ‘verse

shall stand’ because the vital understanding around which the Sonnets are

organised is not based on the illusion that death is time’s ‘cruel hand’. The

Poet guides the Master Mistress away from the consequences of misrepresenting

youth’s relationship to nature and the Mistress.

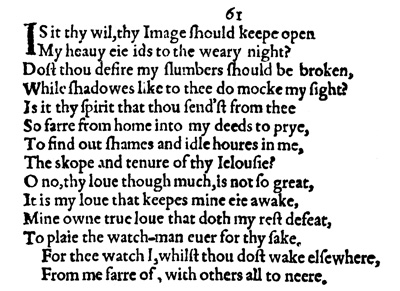

Sonnet 61

Is it thy will, thy Image should keep open

My heavy eielids to the weary night?

Dost thou desire my slumbers should be broken,

While shadows like to thee do mock my sight?

Is it thy spirit that thou send'st from thee

So far from home into my deeds to pry,

To find out shames and idle hours in me,

The scope and tenure of thy Jealousy?

O no, thy love though much, is not so great,

It is my love that keeps mine eie awake,

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat,

To play the watch-man ever for thy sake.

For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere,

From me far off, with others all too near.

Sonnet 61 repeats and develops the thoughts expressed in sonnets 27/28 and

43. The seemingly haphazard distribution of themes throughout the set has

caused many editors to reorder the sonnets by grouping those of similar

theme. Their attempts fail because when one theme is brought into

alignment others are thrown into disarray. How then to account for the

separation of sonnets dealing with the same theme?

The lack of order is only apparent. All the required structure is provided

in the organisation of the whole set as nature, the major sequences as

Mistress and Master Mistress, and the preconditions of the first 19 sonnets.

Truth and beauty, the two logical components of understanding investigated

in sonnets 20 to 126 and sonnets 127 to 154, are inherently structured by

the Poet’s consistent adherence to natural logic. Shakespeare represents the

natural conditions from which the processes of thought are derived. Any

attempt to structure the Sonnets on other principles must fail. Interpretation

of the Sonnets has failed for 400 years because it has attempted to understand

individual sonnets according to the idealised psychological constructs

of traditional philosophy.

In sonnet 61, the sleepless Poet wonders if the ‘Image’ (61.1) that seems

to mock him in the ‘weary night’ forms ‘shadows’ (61.4) transmitted by the

‘will’ of the absent youth. He asks if the shifting shadows are a ‘spirit’ that

pries (61.6) on his activities out of ‘Jealousy’ (61.9). But no, he realises it is

not an image of the youth he sees, rather ‘it is (the Poet’s) love that keeps

mine eie awake’ (61.9). The Poet is playing the ‘watch-man’ for the youth’s

sake (61.12).

In the couplet, the Poet reveals his concern that the impressionable youth

is ‘all too near’ the influence of the inferior Poets, who flatter him with style

and clever rhyme. By contrast, the Poet’s ‘love’ offers an understanding based

on the content of his poetry.

The Poet’s inability to form an image of the youth when lying awake is

the theme of sonnets 27/28. Only when he dreams in sonnet 43 does the

image form. Sonnet 61 recalls the theme and adds a concern about the

youth’s susceptibility to the adolescent influence of the lesser Poets.

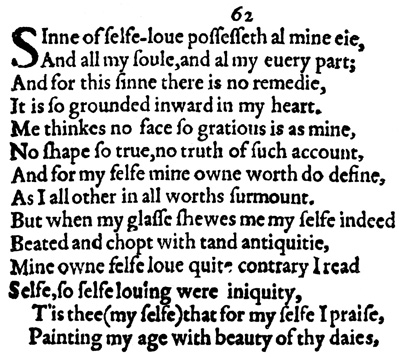

Sonnet 62

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eie,

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Me thinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account,

And for my self mine own worth do define,

As I all other in all worths surmount.

But when my glass shows me my self indeed

Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity,

Mine own self love quite contrary I read

Self, so self loving were iniquity,

T'is thee (my self) that for my self I praise,

Painting my age with beauty of thy days.

If Shakespeare wrote sonnets in the 1590s to a particular youth, sonnet 62

shows something of the transformation that occurred before 1609 as he

welded them into a deeply philosophic statement. While sonnet 62 can still

be read as if addressed to a youth, the addition of ‘my self ’ to the ‘thee’ in

line 13 shows the Poet’s principal object is his youthful self.

The ‘sin of selflove’ (62.1) that consumes him has ‘no remedy’ because ‘it is so grounded

inward in my heart’ (62.4). The selfish idealism of adolescence, with its

counterpart in the male God of religion, is but a formative stage in the development

of the mature Poet.

When the Poet relives his youthful idealism, it seems no face is ‘so

gracious as is mine’ (62.5), and no shape is ‘so true’ (62.6). The sense of

‘worth’, derived from his youthful experience, temporarily ‘surmounts’ or

confounds ‘all (the) other’ (62.8) states of his mature being. But when his

mirror or ‘glass shows me my self indeed beated and chopped with tanned

antiquity’ (62.10) he sees the recurring ‘self love’ as a delusory ‘iniquity’

(62.12).

In the couplet, the Poet sympathises with the inclination to see the

reconciliation of youthful idealism and philosophic maturity as a revival of

youthful ‘beauty’. The Poet’s mature understanding recognises the importance

of youthful vitality, but rejects the iniquity of ‘self-love’.

The conceits of ‘self-love’ and ‘aging’, the image of the ‘eye’, and the

dynamic of ‘truth’ and ‘beauty’ expressed in sonnet 62, were introduced in

the increase sonnets. There the youth was addressed directly. The underlying

message of sonnet 62 deepens the fundamental argument. Shakespeare,

in the later sonnets, shows how the logical combination of idealism, selfevaluation,

and social reckoning based on the increase argument out of

nature, provides the mature basis for an understanding of the dynamic of

truth and beauty.

By writing sonnets that are self-critical and self-affirming, Shakespeare

creates a philosophic standard to which he holds himself accountable. Sonnet

62 can be read as a critique of the role of idealism in society, where juvenile

beliefs have the same delusory power and inherent iniquity as those capable

of affecting the youthful persona of the Poet. The Sonnets argue for a

maturity of understanding and love in which the idealism of youth and the insights

of age are not in conflict.

Sonnet 63

Against my love shall be as I am now

With time's injurious hand crushed and o'er-worn,

When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow

With lines and wrinkles, when his youthful morn

Hath traveled on to Age's steepy night,

And all those beauties whereof now he's King

Are vanishing, or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his Spring.

For such a time do I now fortify

Against confounding Age's cruel knife,

That he shall never cut from memory

My sweet love's beauty, though my lover's life.

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen,

And they shall live, and he in them still green.

From sonnet 20 onward, the underlying thread that frequently surfaces is

the relation established in sonnets 15 to 19 between increase and poetry.

After the 14 increase sonnets establishes the priority of the body, the 5

increase to poetry sonnets argue that the processes of the mind derive

from the bodily processes. Sonnet 18’s ‘when in eternal lines to time thou

grow’st’ expresses the interrelatedness in a single image. The youth’s

genealogical lineage is a prerequisite for the ‘lines’ of poetry.

When examining the various aspects of truth and beauty in sonnets 20

to 154 the Poet resists the temptation to give poetry a value greater than

the bodily processes that make it possible. He does this by using the argument

given precise expression in sonnet 18. Similarly in sonnet 63, he uses the

imagery of the increase sonnets, such as ‘Spring’ and ‘green’, and recalls the

metaphorical use of ‘lines’ (63.13) from sonnets 16 and 18.

The principal focus of sonnet 63, though, is not the increase argument,

but the function of poetry as a means to record an image of the youth before

he begins to age. Poetry does not replace the biological function that enables

the youth to persist to another generation in his offspring. It can, though,

memorialise his appearance and attitudes so that his future offspring can read

of his youthful attributes, and the qualities and failings that contributed to

his uniqueness.

The Poet prepares for the time when his ‘love’ is ‘crushed and o’er-worn’

by ‘time’s injurious hand’ (63.2). When the youth has ‘lines and wrinkles’

and his ‘youthful morn’ becomes ‘Age’s steepy night’ (63.5) and his kingly

beauty vanishes (63.7) removing the ‘treasure of his Spring’ (63.8), the Poet’s

verse will be a testimonial to how he looked.

The Poet will ‘fortify’ youth against ‘Age’s cruel knife’ (63.9) to ensure

that even though his ‘lover’s life’ will go, his ‘sweet love’s beauty’ will never

be ‘cut from memory’ (63.11). In the couplet, the Poet’s ‘black lines’ will

‘live’ because they extol both the ‘green’ of the increase argument and offer

a memorial for the youth’s beauty as poetic compensation for his inevitable

aging and death.

Shakespeare argues that no amount of poetry will turn memory into a

full-blooded child. That is the function of the sexual dynamic. What poetry

can record is the youth’s beauty for posterity to enjoy. The function of poetry

should not be confused with the persistence of life. Bodies need little

encouragement to increase, but it takes continual argument to ensure the

mind does not lose sight of its lines of descent. This is why the greater

number of sonnets (20 to 126) is devoted to instructing the youth in the logic of truth and beauty.

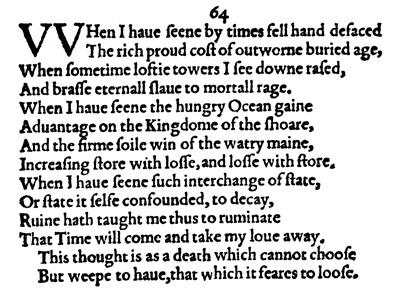

Sonnet 64

When I have seen by time's fell hand defaced

The rich proud cost of outworn buried age,

When sometime lofty towers I see down razed,

And brass eternal slave to mortal rage.

When I have seen the hungry Ocean gain

Advantage on the Kingdom of the shore,

And the firm soil win of the watery main,

Increasing store with loss, and loss with store,

When I have seen such interchange of state,

Or state it self confounded, to decay,

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate

That Time will come and take my love away.

This thought is as a death which cannot choose

But weep to have, that which it fears to lose.

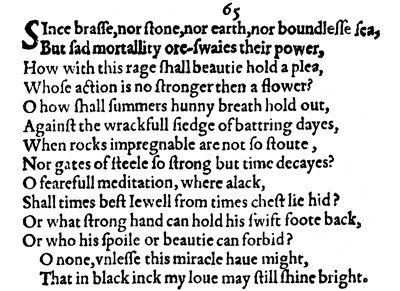

Sonnet 65

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o'er-sways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O how shall summer's honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of batt'ring days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but time decays?

O fearful meditation, where alack,

Shall time's best Jewel from time's chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil or beauty can forbid?

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Comment on Sonnets 64 & 65

Sonnets 64 and 65, joined logically with a ‘since’, continue the critique of

‘time’ begun in sonnet 60 and continued in sonnet 63. They are separated

by sonnets 61 and 62, which make no mention of time. The arrangement

of the sonnets on the theme of time from 60 onwards is consistent with the

organisation of other themes in the sonnet set as noted in the relationship

of sonnets 27/28, 43 and 61.

Sonnet 64 presents a litany of complaint about the inability of any natural

or man-made structure to resist the forces of nature over time. Time

‘defaces’ the ‘rich proud cost of outworn buried age’ (64.2), such as the

edifices built to the ‘dear’ or costly ‘religious love’ mentioned in sonnet 31.

‘Lofty towers’ are ‘razed’ and even ‘brass’ is a ‘slave to mortal rage’ (64.4).

The ‘hungry Ocean’ can gain advantage over the ‘Kingdom’ of the shore.

The ‘firm soil’ (64.7) in turn can win against the watery main showing

that the natural cycle of give and take is evident in the forces of nature.

The Poet further signals his intent in his use of the word ‘store’ (64.8). In

sonnets 11 and 14 ‘store’ expresses the potential for increase. So, the natural

activity of sea and land has its counterpart in the human dynamic.

From the Poet’s observation of the power of nature for such an ‘interchange’

(64.9) in which the natural state itself is ‘confounded’ to ‘decay’, its

pending ruin teaches him that in ‘time’ his love of the youth will also be

taken ‘away’ (64.12). In the couplet, he calls such thought a ‘death’ without

choice, which ‘weeps’ over what it has and ‘fears’ what it will ‘lose’. If an

individual’s life is religiously idealised then death is feared as the end of that

person’s life. But such thought is contrary to the dynamic of nature where

in time such a religious ‘Kingdom’ would erode away.

In sonnet 65, the Poet reasons that ‘since’ brass, stone, earth and sea are

subject to the power of mortality or decay and death, how is ‘beauty’ (65.3)

to hold its own when its action is no stronger than a ‘flower’. The beauty

of ‘summer’s honey breath’ (65.5) seems powerless against the ‘wrackful siege

of batt’ring days’, or time, where ‘rocks’ cannot resist and ‘gates of steel’ (65.8)

are subject to decay.

The Poet then mocks the fear of such a possibility, which so easily leads

to a religious need for ‘fearful meditation’ (65.9). He asks ironically where

can ‘time’s best Jewel’ or the flower of youth be hidden from ‘time’s chest’

(65.10). The Poet begs the question when he wonders what ‘strong hand’

can hold back the ‘swift foot’ of time or who can forbid his ‘spoil or beauty’

(65.12). In the couplet the Poet sardonically suggests a ‘miracle’ may still

foil time, if only that his love will ‘still shine bright’ in his ‘black ink’.

The tendency to read sonnet 65 as a validation of immortality through

verse is countered by the Poet’s sardonic irony. Black ink has less power to

resist the forces of nature than rocks or brass. The ‘black’ irony is that a book

of words would resist time’s hand even less than brass. If poetry was the

means then, as sonnet 11 argues, in ‘threescore years’ the world would be

done away and the poetry be unavailing. It is only through increase that

potentially millions more ‘shadows’ can subtend on the youth. So, as argued

in sonnet 55, it is the ‘content’ of the Poet’s black ink that survives. Nature’s

power to overcome time and death resides in persistence through increase.

The consistent message of the Sonnets that only through increase can

human understanding persist is reinforced in sonnet 64 in the words

‘increasing store with loss, and loss with store’, and through the logic of truth

and beauty captured in the ‘spoil or beauty’ of sonnet 65. The black irony

will be answered in the sonnet pair 67/68 where the word ‘store’ occurs in

both couplets. They affirm that truth and beauty or full human understanding

have their basis in natural processes.

Some editors emend ‘spoil or beauty’ to ‘spoil of beauty’ because they

do not appreciate the oppositional logic of the truth dynamic where true

or false or good or evil are subject to the ‘endless jar’ of debate. Such

seemingly harmless emendations reveal the editors’ inability to see beyond

the inconsistencies engendered by traditional beliefs.

Sonnet 66

Tir'd with all these for restful death I cry,

As to behold desert a beggar born,

And needy Nothing trimmed in jollity,

And purest faith unhappily forsworn,

And gilded honor shamefully misplaced,

And maiden virtue rudely strumpeted,

And right perfection wrongfully disgraced,

And strength by limping sway disabled,

And art made tongue-tied by authority,

And Folly (Doctor-like) controlling skill,

And simple-Truth miscalled Simplicity,

And captive-good attending Captain ill.

Tir'd with all these, from these would I be gone,

Save that to die, I leave my love alone.

Even the black irony of sonnets 64/65 does not prepare the reader for the

unrelenting attack on simplistic idealism in sonnet 66. The Poet recites a

litany of complaints with a persistence that gives sonnet 66 its unique form.

He says he is so ‘tired’ of addressing illogicalities, he would prefer a ‘restful

death’ (66.1). Then he lists a series of contradictions that arise when those

who see no value in life ignore natural logic and seek refuge in an idealised

world of ‘simple-Truth miscalled Simplicity’ (66.11).

As is revealed in sonnets 67 and 68, the youth stands accused of inciting

a litany of misery. But the mature Poet is no longer prey to ‘all these’

(66.1,13) dilemmas. Instead he says he is ‘tired’ of explaining to the youth

that overwrought idealism hides within it the canker that creates such

unexpected outcomes. Although the Poet has matured past the youth’s

simple ideals, he feels a sense of responsibility toward the youth. He cannot

‘leave my love alone’ (66.14). In the youth’s fatalistic view of life, he recognises

his own youthful idealism.

So in sonnet 66 the Poet recites a list of opposing ideas generated when

over-wrought ideals are exposed in the logic of life. He contrasts desert and

beggary, need and jolliness, faith and broken vows, honour and shame,

maiden and strumpet, right and wrong, strength and disability, art and

authority, folly and skill, simple-truth and simplicity, and good and ill. For

each singular ideal or mind-based sensation the Poet shows how beauty as

the ideal, relates to ‘Truth’. Truth as the dynamic of saying, logically entails

an idea and its opposite. When the idealist calls his sensation of absolute or

‘captive’ good ‘Truth’, he prejudices beauty and misnames truth. The Poet’s

logic is evident in the repetition of ‘And’where the litany of ‘Ands’ provides

a practical demonstration of the truth dynamic.

Most readings of sonnet 66 interpret the Poet’s decision not to ‘die’

(66.14) as an act of undying love for the youth. Not only is this a ‘simple-

Truth miscalled Simplicity’, it trivialises the Poet’s intent. When other

sonnets such as 18, 55, 116, and 129 are interpreted as idealistic, the

commentators fall into the trap warned against in sonnet 66.

In Troilus and Cressida, Ulysses states that ‘justice’ resides in the ‘endless

jar’ between ‘right and wrong’. Interpreters of sonnet 66 fail to recognise

the ‘endless jar’ in the give and take between the opposites in each line.

Rarely are ‘all these’ dilemmas evident at one time. In life, one or two may

be of immediate concern. So the Poet contrives the list to explain the

dynamic of truth and beauty to the youth. Only when he appreciates the

dynamic will he understand the content of the Poet’s philosophy.

Sonnet 67

Ah wherefore with infection should he live,

And with his presence grace impiety,

That sin by him advantage should achieve,

And lace itself with his society?

Why should false painting imitate his cheek,

And steal dead seeing of his living hue?

Why should poor beauty indirectly seek,

Roses of shadow, since his Rose is true?

Why should he live, now nature bankrupt is,

Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins,

For she hath no exchequer now but his,

And proud of many, lives upon his gains?

O him she stores, to show what wealth she had,

In days long since, before these last so bad.

Sonnets 67 and 68 should be considered together as they are logically

connected with a ‘thus’, but because they warrant fuller treatment sonnet

68 is considered separately.

The Poet recognises opposing qualities in the idealistic state of mind

typical of youth. The first is the illusion of omnipotence that accompanies

idealised thoughts. Youth imagines it can outwit the forces of nature and

be perpetuated forever in the Poet’s verse. The Poet countered such expectations

in sonnets 64/65. His natural logic addresses the relation between

youthful idealism and the world. The second quality is the youth’s birthright

beauty, which he can potentially pass to succeeding generations. From

sonnets 20/21, natural beauty has been contrasted with ‘painted beauty’ or

‘false painting’. Shakespeare’s sonnets do not require ‘false painting’ for their

expression of truth and beauty.

In sonnet 67, the Poet addresses the consequences for idealism in

‘society’. The youth’s excessive idealism makes him susceptible to the

‘infection’ (67.1), the ‘impiety’ (67.2), and the ‘sin’ (67.3) which ‘laces itself

with his society’ (67.4). But, the Poet asks, ‘why should false painting imitate

his cheek?’ And why should ‘poor beauty’ (67.7) or a misunderstanding of

the logic of beauty, lead the youth ‘indirectly’ or unwittingly to ‘Roses of

shadow’, when by his looks ‘his Rose is true’ (67.8)? The Rose, as the symbol

of beauty, is susceptible to canker when the logic of beauty is forsworn.

The youth’s idealistic attitude has ‘bankrupt’ his ‘nature’ (67.9), ruining

the ‘blood’ that should be sexually alive in his ‘veins’ (compare 109.9 where

‘my nature’ and ‘blood’ are revisited). Instead, he is as good as dead. Nature

then has no ‘exchequer’ or treasure but the youth’s previous beauty. While

many others remain sexually ‘proud’ (67.12), only ‘nature’ (like Venus in

Venus and Adonis) ‘gains’ from his grave.

But, in the couplet, while the youth yet lives, ‘she stores’ him as a

reminder of the ‘wealth she had’ before male-based idealism made these ‘last

(days) so bad’ for the logic of increase. (Some editors emend ‘proud’ to

‘priv’d’, killing off the sexual allusion.)

Here as in sonnet 116 the word ‘cheek’ refers both to the face of the

youth and his sexual parts. If his ‘eye’, or source of truth and beauty, is

blinded (‘steal dead seeing of his living hue’) then the eye of his sex is also

blinded. The ‘Rose’ both refers to his sexual parts and is an anagram for

Eros the God of love. Human nature is bankrupt when its capacity for

increase is ‘beggared of blood to blush through lively veins’.

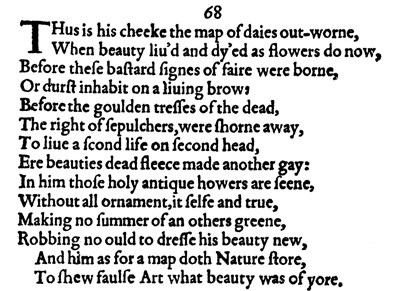

Sonnet 68

Thus is his cheek the map of days out-worn,

When beauty lived and died as flowers do now,

Before these bastard signs of fair were born,

Or durst inhabit on a living brow:

Before the golden tresses of the dead,

The right of sepulchers, were shorn away,

To live a second life on second head,

Ere beauty's dead fleece made another gay:

In him those holy antique hours are seen,

Without all ornament, it self and true,

Making no summer of an other's green,

Robbing no old to dress his beauty new,

And him as for a map doth Nature store,

To show false Art what beauty was of yore.

Sonnet 68 begins with ‘thus’ as it develops the logic of sonnet 67. It repeats

the image of the ‘cheek’ (68.1), reinforcing the connection between the face

and the sexual parts. ‘Thus is his cheek the map of days out-worn’ relates

the beauty of the youth’s face (‘map’ also meant face), which has survived

for generations, to the sexual parts through which he has been able to

survive. Sonnet 68 uses the image of a ‘map’ or pattern to convey the sense

of the youth’s sexual potential as a ‘store’ (68.13) for future generations. In

Shakespeare’s ‘society’ (67.4) biblical beliefs had discredited the idea that

Nature ‘stores’ the ‘wealth’ of humankind in natural processes.

So in sonnet 68, the youth’s beauty derives from natural processes,

harking back to the times when ‘beauty lived and died as flowers do now’

(68.2). ‘The bastard signs of fair’ are those false representatives or idealised

entities who dare (‘durst’) ‘inhabit a living brow’ (68.4). Although the youth’s

idealistic beliefs alienate him from nature, she still insists that the logical way

to increase is by mapping from his ‘cheek’.

The Poet then considers the consequences of denying natural logic.

‘Golden tresses of the dead’ (68.5), which should remain in ‘sepulchers’, are

used to fabricate ‘a second life’ on a ‘second head’ (68.7). ‘Beauty’s dead

fleece’ is mis-used to make ‘another gay’. Despite the charade, the youth has

the potential, available in his natural inheritance or ‘holy antique hours’

(68.9), not to rob the ‘old’ to dress ‘his beauty new’ (68.12). Shakespeare

uses biblical imagery to mock Christianity’s life-denying beliefs.

The couplet reinforces the imagery of the map from line 1 and recalls

the couplet of sonnet 67. Nature ‘stores’ the youth as if a ‘map’, as Nature’s

pattern provides the standard for ‘beauty’ against which the ‘false Art’ of

over-inflated ideals is compared.

Sonnets 67 and 68 are misunderstood when viewed from the prejudice

of beliefs that do not recognise the logical relationship between the

persistence of life and the limitations of the ideal. When editors retain the

original spelling of the word ‘borne’ (68.3) but convert all the other words

to modern spelling, they limit the meaning of ‘borne’ to that of carried. In

some editions a further interference occurs in sonnet 67 where the ‘seeing’

of line 6 is altered to ‘seeming’ destroying the significance of the ‘eyes’ as a

double-cheeked source of truth and beauty.

The double meaning of the word ‘Rose’ as the symbol for beauty and

as Eros, and the use of the word ‘store’ make these two sonnets particularly

significant. They point to nature and the increase sonnets as the foundation

on which the mythic meaning of the whole set is constructed.

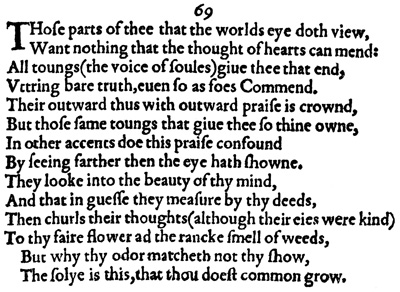

Sonnet 69

Those parts of thee that the world's eye doth view,

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend:

All tongues (the voice of souls) give thee that due,

Uttering bare truth, even so as foes Commend.

Their outward thus with outward praise is crowned,

But those same tongues that give thee so thine own,

In other accents do this praise confound

By seeing farther than the eye hath shown.

They look into the beauty of thy mind,

And that in guess they measure by thy deeds,

Then churls their thoughts (although their eyes were kind)

To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds,

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this, that thou dost common grow.

Every attempt to re-organise the Sonnets has failed to improve on the

original arrangement of 1609. The attempts fail because the meaning of

each sonnet in Q depends on the philosophic structure of the whole set and

the influence of the structure on the logic of increase and truth and beauty

dynamic. The sonnets appear disordered or partially ordered only to those

who are ignorant of their inherent logic. By adhering to his consistent

philosophy, Shakespeare can organise the sonnets to reflect a number of

topics without losing coherence. This freedom to create patterns or concentrations

of meaning also applies to small groups including connected pairs

such as 69 and 70.

Truth in the Sonnets is the perpetual dynamic between saying what is

true and what is false. Beauty, by contrast, is a singular sensation, whether

from the world or of the mind. Sonnet 69 mentions both ‘truth’ and ‘beauty’

but here Shakespeare demonstrates how they exchange meanings under the

influence of the youth’s idealism.

The Poet purposefully misrepresents the meaning of ‘truth’ when he

views the youth’s ‘beauty’ as a singular or ‘bare truth’. If ‘those parts of thee

that the world’s eye doth view’ (69.1) cannot be mended by the ‘thought

of hearts’, the consequence is an utterance or singular exclamation from ‘all

tongues (the voice of souls)’ (69.3), whether from friend or foe. In effect

they sigh or moan to give the youth’s ‘outward’ parts ‘outward praise’ (69.5).

(For a comment on end/due (69.3) see the following sonnet.)

But, the Poet adds, the ‘same tongues’, when they use other ‘accents’ or

say otherwise, ‘confound’ the sounds of praise (69.7). Those who look into

the youth’s ‘eye’ (69.8), to measure the ‘beauty’ of his ‘mind’by the standards

of his outward beauty, are ‘confounded’ by his deeds (69.10). ‘Their

thoughts’ (69.11), or the dynamic of truth, recognise an inconsistency in

his actions. His deeds are selfish because his mind does not acknowledge

the relation between his mind’s ‘eye’ and the ‘eye’ of his sexual parts.

Consequently, the ‘churls’, the critical ‘tongues’, ‘add the rank smell of

weeds’ to the ‘fair flower’ of those parts.

In the couplet, the Poet affirms that external beauty cannot hide the truth

or ‘soil’ that the youth does ‘common grow’ through increase in nature.

Despite his ideal beauty the youth is subject to nature’s laws. The ‘world’s

eye’ that ‘views’ the youth finds he ‘wants nothing’by way of outward ‘parts’.

But when that ‘eye’ looks through the youth’s ‘eye’ into his ‘mind’ and ‘deeds’

he is found wanting.

Back to Top

Roger Peters Copyright © 2005

Introduction

1-9

10-21

22-33

34-45

46-57

58-69

70-81

82-93

94-105

106-117

118-129

130-141

142-153

154

Emendations

|